The Town of Jobner

by Dr. K.L. Kamat

First Online: January 03, 2005

Page Last Updated: December 07, 2024

As soon as I walked out of the campus I heard young students singing in chorus from a building that looked like a choultry (a large building commonly rented out for weddings and other special events). It however became obvious that this was actually a school. The pupils wore coats, dhotis, and shoes that were shaped like parrot-beaks. They were sitting on the floor and reading aloud. The pundit with long hair and holy ash had to be the teacher. To my surprise, I found that the school did not have a roof! Some generous man must have built this school and run out of funds before it was completed; or a government contractor might have used bad material, causing the roof to be blown away. How unjust! The neighboring college spends 15,000 rupees for a single college day, while just ten percent of that money would have sufficed for the school roof. I regretted that the people of the town did not think like I did. In the meantime, another teacher from another room took the students out for some physical exercise. The hungry children wore torn clothes and took care not to tear the clothes any further. Their clothes had probably been passed on to them from their older siblings. Yet another classroom was in session under the shade of a tree. I wondered what they did in the winter and during the rains. I could see a clock and a radio in what probably was the principal's room. Some privileged students were probably bringing them in everyday and taking the gadgets back with them for safekeeping at night. At this point, a student came out and banged on a hanging metal motor-wheel, as if to indicate the change of periods. The boys rushed out of classrooms like a band of monkeys attacking a banana field. The desert mother seemed capable of absorbing all their urine. The more well-to-do children bought peanuts, chakri, and panipuri from street-side vendors. They were tailed by their less fortunate friends for a small share. A boy greeted me, "Master Sahib, Namaste." Then everybody started greeting me and began following me. They seemed to think that anyone wearing shoes and clean clothes was a respectable master sahib.

In the opposite building, elderly ladies were going inside. Since they were not wearing any jewelry or colorful clothing, it was apparent that they were widows. They had come for a group prayer and Bhajans (devotional songs sung in groups). I could not see what was going on inside. Outside the building sat a sadhu in saffron clothing.

The next building was full of lights, even though it was a bright day, indicating that it was the office of the electricity department. The employees did not seem to have any work to do, and they were singing traditional songs outside. I was told that once a month these employees go from house to house collecting dues and that this was the only work they did. If someone did not have money, they would disconnect the power right on the spot and it would require a bribe of five rupees to restore the connection.

I walked some distance and saw fields on either side of the road. A farmer was watering his crops. Behind him, at a little distance, people were cremating a body. The dead person’s relatives and friends were mourning their departed companion, and the barber was shaving someone's head, as required by Hindu custom. The vultures circled overhead, waiting for the people to leave. I walked on further and saw a chungi (tax collection booth). This had a sign that declared that no vehicle could go further without paying toll. This booth did not have walls, but only a thatched roof. The clerk seemed to be of the opinion that he should not be wasting his best clothes at work, and therefore was wearing a banian (Indian undershirt made of cotton) and long underwear. The banian had so many holes in it that it resembled a fish-net . He did not have a desk and instead conducted his business from his charpai (cot). After he was convinced that I was not a motor vehicle, he let me go through.

To the north of Jobner is the Aravali mountain range. They have built a water canal around the town so that it will not be flooded. My road crossed this canal and turned into a mud road. I saw a woman weaving yarn with a charka (hand-operated spinning-wheel) just like Mahatma Gandhi's. I later saw a three storied summer palace (hawa-mahal,) where there were cows and camels tied to the wall. There was a temple too, on top of which a family lived. The well nearby had gone dry.

I encountered a woman washing dishes. She would pick up a soiled dish, pour fine sand on it, and wipe it with a cloth. After this the dish started glittering again. Before seeing this, in all my life I had thought that only wool and silk were dry-cleaned. A neighbor threw some garbage outside her yard, onto the road. A small battle ensued among the few dogs and pigs in the vicinity. Although the pigs were more in number, the dogs were more fearsome and chased them away. I then walked past a dhobhi's (washerman’s) house. The daughter-in-law was drying a customer's rumal (handkerchief) while her elderly father-in-law was dye-casting designs on another garment. Since Rajasthanis sand-clean clothes rather than wash them, the clothes tend to lose color rapidly. As her family worked, the mother-in-law cooked rotis (unleavened bread) and nagged her daughter-in-law about trivial matters. The next door neighbor was preparing panipuri to sell to school children.

As I walked past a clean-looking house, a gentleman stood up in greeting and introduced himself as the watch repairman of the town. I was to realize later that although his fees were very reasonable, his repairs did not last very long. Then to my surprise I found a bakery selling bread, butter, and biscuits (cookies). The owner of the shop spoke to me in English, "My name is Gyanchand Tiwari; I'm a clerk at the college. I run the shop more as a service to the Sahibs." He suggested that I become a member of his shop for fifteen rupees a month, for which he would supply fresh bread from Jaipur. The next two buildings were run down. The Harijan (low caste Hindus) colony was located beyond this. There were a lot of hogs running around, trying to escape from the boys' attacks. As I watched, four boys pounced upon a big boar and the fifth one shaved him quickly. I learned later that there was a big demand for pig-hair in a nearby factory that produced brushes for artists.

I was alarmed to find a shopkeeper hammering away at a pretty damsel's feet. When I came closer I realized that he was merely tightening her two-ounce silver toe-rings. An elderly man was melting red lacquer and molding it into bangles. His wife was attaching decorations on to the bangles using a pair of forceps. I admired the beautiful artwork, which cost so little. A boy in the household collected the broken bangles and proceeded to re-melt them. I realized that unlike glass bangles which once broken are gone, bangles made of lacquer have an eternal life.

© K. L. Kamat

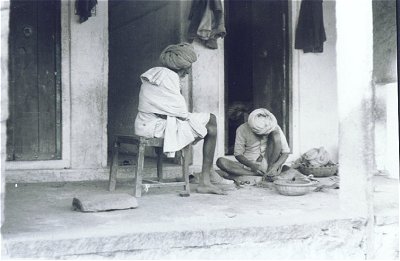

The Village Cobbler

Cobbler repairs footwear as the customer waits. The town of Jobnair, Rajasthan

I walked through the Regar's (craftsmen) colony. The leather-worker was drying leather in the sun. The shoes he was selling did not appear to have left and right identities. I thought this was a nice solution to the problem of losing one shoe at a temple, or a dog's chewing it away. I also noticed there was no difference between men's and women's shoes. His young children were sewing leather with wax covered twine. His neighbor, on the other hand, had to be an expert on camel saddles. He had built saddles of various kinds, each decorated with the utmost artistry. Some even had innovations, such as protection against slipping, room for large seats, etc. His ancestors must have practiced the same trade for hundreds of years.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

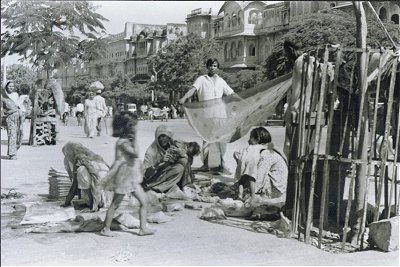

Tie Dyeing (Bandani) of Sarees, Rajasthan

Another street had a pair of bulls going round in circles, announcing that I had arrived at the village oil vendor's. Customers were waiting to purchase freshly extracted mustard oil. Some had brought their own recipes. The next interesting thing I saw was a flour mill. I could tell that the man who had brought soji (cream of wheat) was poor while the one who had brought wheat for grinding was a wealthy man. I was glad that the grinding fee was only two paise per kilogram. However, the owner explained to me that he additionally took away five percent of the grains as his bounty. I walked on to find hens running around. This told me that I had arrived in the Muslim neighborhood. Spotting me, the women-folk gossiped among themselves about the newcomer. Several men were busy weaving cloth and coloring attractive designs on them. This type of Rajasthani bandni saris are very famous.

I was getting hungry and had to return home.

______________________________________

- Excerpts translated from the Kannada original "Na Rajastanadalli," by Krishnanand Kamat, Akshara Publishers, 1974.

- You can find brief descriptions of some of the words in the Glossary

- The experiences occurred in the year 1965.