Temples of West Bengal

First Online: August 15, 1997

Page Last Updated: January 13, 2026

Bengal has been the home of several great civilizations (see: a brief history) . However, structural records of these kingdoms, considering the extent of the country, are extremely scanty. This is largely because of the nature of the soil and the climate, both of which encourage the rapid growth of thick vegetation which is destructive to deserted buildings. However, it is believed that hand of man has played a bigger part in demolishing ancient cities and temples.

Of the ruined temples in the districts of Bankura and Burdwi, enough remains to establish its kinship with the architectural movement in Orissa that produced the temples at Bhubaneswar. The dilapidated temples built by the Bhanja rulers at the ancient site of Khiching in Mayurbhanj provide a connecting link between Orissan architecture of the 11th and 12th centuries and its provincial phase in the south of West Bengal. A distinctive feature of the latter, as of the structures at Khiching, is the absence of a mukhamandapa or portico.

© K. L. Kamat

Terracotta relief, West Bengal

A group of temples at Barakar in Burdwan are believed to have been built in the 10th and 11th centuries A.D. by the Pala kings. These are locally known as the Bengania group on account of their fancied resemblance to the fruit of the egg plant. The Siddheswara temple at Behulara in the Bankura district dates from the 10th century and is the most ornate of this group. Terra-cotta reliefs adorn its entire brick surface, but the lavish decoration merely emphasizes the elegance of its lines. Along with the building movement described above, there was an indigenous style of building, approaching a kind of folk architecture, which was widely prevalent in southern Bengal. Characterized by a freshness and spontaneity, this type of structure was clearly derived from the thatched bamboo hut so common in most parts of Bengal. The curved cornice and eaves, which are a special feature of these temples, are directly descended from the bamboo framework of the huts of the people, originally bent into this shape in order to drain off the frequent, heavy rain. Vishnupur in the Bankura district has a group of such temples, undoubtedly built during the days of the Malla Rajas, who are known to have encouraged temple-building. The Lalgiri temple is built in laterite, has a single tower, and probably dates from 1658. The Madan Mohan temple is in brick and was erected in 1694. The Shyam Rai (1643 A.D.) and the Madan Gopal (1665 A.D.), built in brick and laterite respectively, have five towers each and are of the panchayatana type. The external decoration of these temples, particularly of those constructed in brick, consists of square panels of terra-cotta reliefs, the subject matter of which is often secular and thus of considerable sociological interest.

The jor-bangla or double temple is a structural variation of the same type and resembles two thatched huts joined together and surmounted by a single tower. The Krishnaraya temple built at Vishnupur in 1726 A.D., and the Chaitanya temple at Mayapur (see: an interview with an ascetic at the Chaitanya temple) - in the Hooghly district are typical examples.

A single hall or thakurbari, on one side of which is the vedi or altar, is the main feature of the interior of these buildings. Above this is an upper gallery running round the of the thakurbari. The Hindu-Buddhist movement which produced the enormous monasteries in the Gangetic region towards the end of the first millennium, also extended its influence to Bengal. The remains of a monastery of gigantic proportions have been excavated at Fliharpur in Rajshahit (now in Bangladesh). This vihara was built by the Pala ruler, Dharampala, in the late 8th century. It is said that the followers of Buddhist, Hindu and Jain creeds thronged to this monument. This is corroborated by the terra-cotta statues on the exterior faces of the terraces, which depict in bas-relief the mythology and folk-lore associated with all three religions.

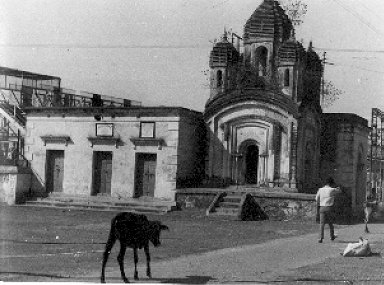

© K. L. Kamat

A terra cotta temple

Lakhnaut, now an obscure ruin near Malda, was once the head and cornerstone of an important school of architecture which came into prominence with the Pala and Sena dynasties. The temples at Lakhnauti, which was the capital of the Sena rulers, were built of black basalt obtained from the neighboring Rajmahal hills. These ornate structures were despoiled by the Muslims in 1197 and their remains were used to build a Muslim capital, at Gaur. From the sculptured stones incorporated in mosques, it can be inferred that the temples of Varendra (Northern Bengal) were similar in many respects to the Manabodhi temple at Bodh Gaya. From the carved stones built into the masonry of the mosque at Gaur and Pandua, it is clear that under the Sena kings there flourished a school of plastic art, which had few equals in excellence of design and execution. The Adina mosque at Gaur also reveals that the masons of the Vishnu temples of the 11th and 12th centuries cemented layers of stones by means of molten metal. In what is now the mosque of Zafar Khan Ghazi at Tribeni in the Hooghly district, two compartments have been identified as the antarala (sanctorum) and mandapa of a Vishnu temple of the Lakhnauti style, and therefore of the Pala-Sena period.

Of the comparatively recent temples near Calcutta, that of the goddess Kali in the Kalighat area, the Dakshineswar temple where Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa was once the priest, the Belur temple, four miles north of Howrah, and the Vishnu temple at Bansberia (1679) are noteworthy. There are four Jain temples built in the late 19th century in Badridas Temple Street in Calcutta. The most important of these is dedicated to Shree Sheetalnathji, the 10th of the 24 Jain tirthankaras (deities).

![]()

See Also at Kamat's Potpourri

- Temples of Rajasthan

- Hinduism Potpourri -- Hindu Gods, thoughts and mythology

- Banga-Darshana -- West Bengal Topic Index

- Temples of India

References

- The Temples of India - Department of Information and Broadcasting, The Government of India