Town of Mundatikara

Previous story: The town of Chotedongar

The Town of Mundatikara

Once upon a time, the forest south of Narayanpur was known as impenetrable because of its ferocious valleys, wild life and dense trees. The last place you can reach by bus is Chotedongar; after that, one can only walk. Mundatikara (a.k.a. Mundatikra, Mundatikada) is a tribal locality about two miles from Chotedongar. The lakes and ponds of Mundatikara were bursting with energy when we went there. It appeared that the menace of wild animals was rampant. The people paid more attention to the fences than to their houses. The household animals were put on the second floor of the habitat where the room was less so they had to be cramped.

© K. L. Kamat

"Did you come from Jagadalpur?" When I said no, he thought I must have come from Raipur. When I told him that I came from even farther than that, he assumed that I was from Bhopal. There was no way I could tell him about Bangalore or how far it was from there. Someone brought a Katia (small cot) from inside and let me sit down. The barks of the tree were woven into the body of the cot. "Now you are in the poor people's world. We do not get nylon or jute stripes here; neither can we afford them. This Katia is designed to fit into my bullock cart. That's why it's asymmetrical." The man explained the discomfort of the Katia. When I told him the purpose of my visit, he was happy that I had come from so far. In our honor, the ladies supplied tea without milk. When inquired about the lack of milk in the tea in spite of all the cows and lambs, I was told that they believed that cow's milk was meant solely for the calves, and they consumed milk for the sake of elderly and children only. They even told me that if some extracted milk remained after consumption they would feed it to the calves. "We eat meat and fish, but the cows can eat only grass. Since we cannot afford nutritional food for the cows (like cotton seeds), we let them enjoy their mother's milk", the villager explained. I was amazed at their concern for the animals, and could not decide which one between the adivasis and the modern world was more nature conscious.

I looked at the Tulsi in the courtyard and asked Kurma, the village head, if they worshiped Hindu gods. I told him that I had heard that the adivasis (tribals) worshiped their own. "Somebody has given you the wrong information; all the tribals in this town are Hindus. We are the most advanced of the tribals and have been practicing the religion since a long time. Our Halbi language has a script and has literature in it. We are very advanced, but do not want to lose the tribal status the government provides us." Kurma explained. Many other men joined the conversation. What was peculiar was the way they were standing: on one foot just like a crane.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

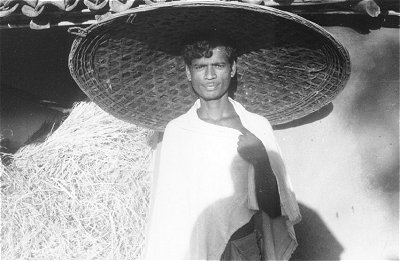

Gigantic Hat Made with Hay Straws

Kurma showed us his house. The house was very neat with grass roof; they had no shortage of wood fuel and the stove was always running whether cooking was being done or not. The stove served as a heating mechanism at night. All the groceries were hung from the roof in baskets. So was a cradle with two children, who were fast asleep. The prayer room had several idols and was decorated with sandal wood paste, fresh flowers, and Rangoli. Kurma showed me a big pot, and said it was full of castor oil which they used as fuel for the lamps. Then we went to the farm; they grew all kinds of vegetables (pumpkin, spinach, sour mango, etc.) and fruits there. There was a huge hat hanging on the wall; I wanted to try it. It was as big as the one to fit Ravana, the man with ten heads. How can anybody work with this hat on? I asked. Kurma smiled and put it on my head. It was feather light! I mused myself with the thought of wandering around in Bangalore with the hat.

Then he told me that he'd take me to the factory! It was a hut. They flaked the rice there. Without any light, there was an old woman who was pushing the rice stamps into a big wheel pulley. Her granddaughter separated the rice from the dust. Although dusty, she was an attractive, innocent beauty. She was wearing a necklace made with silver coins. She was wearing a mini sari although her age called for a frock. She just couldn't resist the temptation to look at us although she was busy at work and my camera did its job.

Now Kurma wanted to be photographed; he posed in front of Tulsi, his children, with the hat, and with the cows. His wife adoringly looked at her husband as if he were giving a performance. Then I wanted to photograph her, but she ran inside; she was shy. I volunteered to photograph Kurma's brother but he wanted to change clothes for the photos. I was greatly disappointed when he returned; he was wearing the blue uniform that was distributed at the coal mines. "He has passed his 10th grade exam. It does not befit his education to wander around with bows and arrows, right? But, he could not get a job. With a lot of political influence, we managed to appoint him as a forest guard." Kurma justified the uniform.

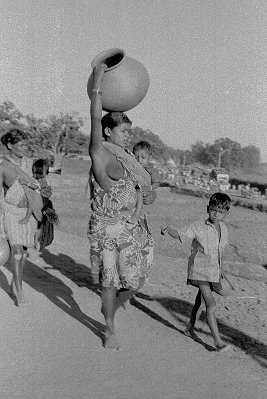

Kurma's brother wanted to be photographed with his wife; apparently the children in cradle were his. He ordered his wife to come and pose for the photo. The poor thing was feeding the baby, and came just as she was. He got angry at her and chased her inside. She returned with a blouse that didn't fit; she covered it with her sari. An elderly lady came just to see how the daughter-in-law looked in blouse and sari. She was wearing interesting combs which I documented. They made sure I wrote their addresses and mandated to send multiple copies of the photos.

![]()