The Ideal of Ornament

Page Last Updated: December 07, 2024

Ornamentation not only serves to please the eyes of the beholder but also fulfils an auspicious purpose. Thus, the impulse to adorn stems from a deep rooted sensibility to mark every occasion of life with auspicious symbols, designs and figures to obtain good fortune and protection from evil.

The Sanskrit term for ornament used by generations of Indian aestheticians is alamkara which broadly encompasses poetry, drama, music, philosophy and the visual arts. Although, in common parlance, the term alamkara would simply connote bejeweling, it has a farther reaching significance as an element of literary criticism. The genesis of this term has been traced back to the Vedic period where its meanings range over the notion of adornment, beautification, ornamentation, enhancement of grace or beauty, to invigorate or make fit for a purpose.

© K. L. Kamat

The Hoysala Ornamentation

Literary flourishes in Sanskrit prose and poetry are enriched by alamkara like upama (simile) and rupaka (metaphor) and so on. They enhance the meaningfulness of aesthetic concepts such as dhvani (suggestivity), rasa (sentiments) and reeti (literary style). The use of metaphorical symbols in the visual arts of India is a phenomenon, inseparable from the concept of alamkara. This symbolic imagery inspired by poetry, led to the illustration of folios of manuscript painting employing visual metaphors which in turn allude to literary metaphors. Indian sculpture also developed an analogous concern for the symbolic representation of abstract visual concepts such as fertility (mother goddess figurines), rain (Indra), water (Varuna, Ganga-Yamuna), earth (prithvi), creation (lingam-yoni,Vishnu-Seshashayi, brimming pot or purnakalasha etc.) which were identified by their natural visual quality and impact on human life.

Historically important to the study of ornamentation is the concern shown by the western cultures and their contribution to the recognition, popularity and survey of Indian decorative arts. The discovery of the Indian arts and crafts by the officers, surveyors and archaeologists of the East India Company and the British Raj and their subsequent display at the India Museum in East India House around the first half of the I9th century was a remarkable event. Indian decorative arts were for the first time carefully studied, collected and appraised with the result that not only in England but all over Europe, they influenced the public taste and excited the sensibilities of designers. Even the historians of design like Owen Jones and John Ruskin took note.

The discovery of the Indian decorative arts and crafts came about at a time when the West was disillusioned with industrially finished products; hand made objects fashioned from individual imagination with the human touch were desired. The Great Exhibition of 1851 showed for the first time in the West several Indian decorative objects produced in various materials. Several such exhibitions subsequently held in America, Australia and parts of Europe opened the eyes of the western world to the quality, beauty and sophistication of Indian designs, craftsmanship and materials. The South Kensington Museum, London collected Indian arts and crafts and utilized it for training designers and architects.

Another development was the use of Indian decorative motifs on colonial buildings designed by architects such as Robert Chisholm towards the end of l9th century. In 1904, George Watts and Percy Brown brought together a major exhibition and catalogue of Arts and Crafts of India at Delhi. Indian arts and crafts were thus systematically documented and catalogued for the first time.

Art historians of the late 19th and early 20th century have played a valuable role in studying decorative motifs from the point of view of psychology of design, evolution of motif and its symbolic interpretation. By the efforts of scholars such as Alois Reigl, Gombrich and many others, the subject of ornamentation has gained access to the level of serious art historical research.

Ornamentation, as a stylistic sensibility in art and literature has an interesting history, for which evidence is available equally in archaeological remains and living tradition. From the age of prehistory, art followed life and the pen and chisel of master artisans, the nimble fingers of Indian housewives, the warp and weft of masters of the loom created new motifs or repeated older extant ones giving rise to an entire vocabulary of ornamentation. Out of this vast vocabulary, one can identify several motifs which have remained unchanged over the centuries, while others have evolved and completely metamorphosed.

© K. L. Kamat

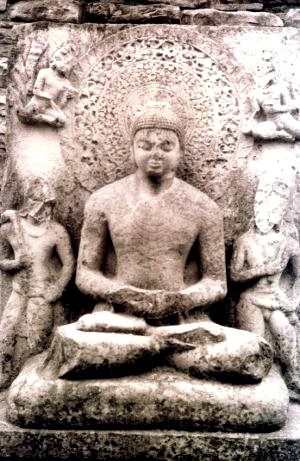

Statue of Meditating Buddha

The Sanchi Museum Collection, Madhya Pradesh

Motifs such as the lotus, the brimming pot, the arabesque and the crocodile with foliate tail have been chosen here to represent the most typical motif types favored in Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic and Southeast Asian art. They share a common fluvial origin, but their placement, form and semantics have varied greatly across religions and cultures, through different periods. The origins of most of the motifs can be traced to the Buddhist monument of Bharhut of the Shunga-Kushana period. The aquatic and vegetal motifs found at Bharhut arise from nature worship and notions of fertility. Reproductive power, regeneration, abundance and prosperity represented by these motifs glorify the dependence of human life on nature. These motifs arising in folk culture were slowly absorbed into the mainstream religions as vital principles. Visually many of the motifs can be read as decorative patterns but at source, their meanings are quite distinct.

The meaning of kalpalata or the arabesque originated from the concept of the ever-growing creeper of prosperity, twining around on its perennial growth route, teeming with treasures which human beings yearn to obtain all their lives. The placement of this motif varies in every religious monument. On stupas of the Buddhists and Jains, they are found twining around the anda (hemispherical dome of the stupa), in Hindu temples, kalpalata is found on the doorways, walls, plinth and the perforated windows and on Islamic monuments, they run all around the facade, the mihrabs and the archways.

The dissemination of one motif type and its adaptation in different religious monuments over several centuries suggests that the motifs were passed on from one generation of craftsmen to another and many of these motifs have remained in oral or mental forms and have not been standardized in a textbook for open reference.

Finally, what is significant in this whole study of motifs such as the kalpalata is the presence of this motif on monuments, decorative arts, arms, jewelry, textiles, folk and tribal arts and crafts. In other words, the same motif is translated and transformed from medium to medium. This sharing of patterns and designs unifies the artistic, philosophic and creative vision of the Indian artisans and designers.

![]()