Kings, Courtiers and Craftsmen

Page Last Updated: January 13, 2026

Travelers to the Maurya (c. 322-183 B.C.) court returned to their countries with tales of opulence and of palaces decorated with teak and ivory. Although meant to illustrate Buddhist legends, the Ajanta cave murals (painted during the Gupta Vakataka period, 4th-6th century) could very well be a visual record of the luxury and pomp of the royal court. The murals depict gods and holy men with the finest trappings of royalty, attended by courtly retainers and bejeweled dancers.

In ancient India, kingship was an important office which entailed heavy public responsibility. Hindu legal texts, set out the ideal that the king was expected to aim for. The Arthashastra, for example, lists the standards of royal existence, from the daily activities of the king, his moral and public duties, to the qualities of his courtiers, councilors and servants. Numerous poets, painters, musicians and learned men also dwelt in the palace and enjoyed royal patronage. The brahmins or priests were among the most honored members of the court.

© K. L. Kamat

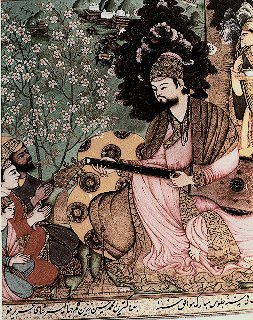

The Mighty Mogul emperors

(Left to Right) Jahangir, Akbar the great, and Shah Jahan (who built the Taj Mahal)

The Muslims in India took court ceremonies a step further, and kingship became more absolute and sacrosanct. Religious prostration, which entailed kissing the ground before the sultan or kissing his feet, was customary. As an indication of the reverential attitude towards kings, prostration before the empty throne was even practiced by the Muslims. This was also clearly suggested by the depiction of the halo in royal portraiture. The emperor Akbar (1556-1605) later introduced other forms of salutations such as placing the right hand upon the forehead and bending the head downwards.

Court ceremonies were formal and pompous affairs. The officials and ministers were given fixed places to stand and a master of ceremonies maintained order and precedence in court. Amidst the imperial insignia of a gold mace and gold tiara adorned with peacock feathers, the chief usher proclaimed the presence of the sultan. Such elaborate ceremonies were intended not only for the glorification of the rulers, but were also meant to impress the local nobility and foreign dignitaries who regularly streamed into the courts to pay tribute and present gifts to the king.

Like the Hindu rulers before them, the Muslim sultans were expected to fulfill important public duties. In the hall of general audience, the sultans heard petitions, dispensed justice, conducted state affairs, and received foreign guests as well as defeated enemies. Here, reports of ministers and officials were presented. Here too, musicians, poets and learned men showed off their talent and intellectual discussions were conducted. Proving himself to be less detached and aloof than previous monarchs, Akbar appeared every morning before the assembled crowd either at the window or the balcony.

A typical court had not only its usual entourage of courtiers and literary scholars, but also an assemblage of highly skilled artisans. Indeed, it was primarily due to the patronage and financial support of royalty that some of the most splendid examples of art and architecture in India were created. Sculpture, painting and the decorative arts were commissioned to bolster the magnificence of the courts and the sovereignty of kings. Hindu rulers also believed that they would acquire merit by commissioning religious works of art. The Moghul emperors (1526-1857), in particular, were ardent patrons and connoisseurs of the arts. The Rajput maharajas, who had spent varying periods at the Moghul court after their subjugation, were influenced by the opulence they saw and began to commission decorative arts for their courts, some of which were no less inferior to those of the Moghuls in terms of their quality and sophistication.

© K. L. Kamat

Adil Shah II playing tamboor

The courts of the Moghuls, as well as the Deccani (1500-1868) and Rajput rulers, had workshops attached to them. Some of these workshops (known as karkhanas or manufactories in the Muslim courts) were situated within the palace walls while others were established in cities away from the capital where local craftsmen were readily available.

The most skilled craftsmen were employed in the karkhanas and they were mostly indigenous workers. Such was the value of craftsmen that when Timur massacred the inhabitants of Delhi in 1398, he spared the Indian craftsmen and recruited large numbers into his service. The local artisans employed in the karkhanas were either converts to Islam or were former slaves. Moghul-trained Muslim artists also entered into the service of the Rajput courts. The number of foreign craftsmen who came to India was fairly small. Many of the foreigners who were employed in the royal workshops were highly skilled craftsmen who usually acted as the guide and teacher of their local counterparts. Akbar, for example, employed Persian masters to train Indian artists in the atelier that he founded. During Jahangir's reign (1605-1627), European and Persian artisans entered into the ranks of the karkhanas. In this way the expatriates did exert some influence on the style and decoration of objects, as is evident from the artworks of this period, which show discernible European and Persian elements. As they were expected to attain a high standard of excellence, the craftsmen in the royal workshops were closely supervised. Jahangir, for example, personally selected his craftsmen, and sometimes even oversaw the production of their work.

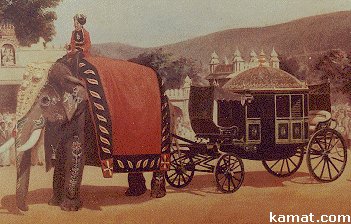

© K. L. Kamat

The Royal Procession

From a Painting on the wall of Mysore Palace

Given the specialization of craftsmen and the fact that skills were often passed down from father to son, the production centers in the various regions came to specialize in a craft or technique which, in time, had come to be associated with that region. For example, Bidar in the Deccan was famous for its bidri (metal with silver inlay) industry while the Kotah region in Rajasthan was well known for its resist dyed fabrics. The materials from which the objects were made as well as the degree of sophistication and ornamentation were important indicators of the wealth and standing of those who commissioned them. Thus, objects made of jade and gold were usually produced for the Moghul court. Imperial items were also generally more ornate and spectacular than those made for the other Indian courts. The finest articles produced by the royal workshops were usually given away as gifts or were used for ceremonial purposes. However, functional objects such as weapons, carpet weights, huqqas (a traditional instrument of smoking using coal, water and tobacco) and drinking vessels were just as elaborately designed and ornamented. Indeed, it is sometimes difficult to tell whether an object was made explicitly for a utilitarian purpose or for a purely decorative or ceremonial function.

![]()