Women in Tribal Societies of India

by Dr. (Mrs) Jyotsna Kamat and Dr. K. L. Kamat

First Published: Year 1980

Introduction

Who is a tribal? The definition may vary with the purpose for which it is required. A politician in India with a palatial bungalow, car, color television, video set, and a fat bank balance could still claim to be a tribal, just because his fore-fathers happened to belong to a government-recognized tribe. He might have used that humble origin of his to amass enormous wealth by exploiting the system. His entire family, including the women, may pretend to be ultra-modern and display much artificial sophistication in their dealings with others. Since such neo-tribals are increasing in number, it becomes very difficult to study genuine tribals who from time immemorial have been true to the nature.

The tribals of India have been in contact with other people for a very long time and have been greatly influenced by them. The degree of influence is proportional to the intermingling with outsiders. Tribes-people like the Gond, Bhil, and Halbi almost live like Hindus do in the outside world. After independence (1947), due to various developmental and welfare projects executed by government and social agencies, it has become extremely difficult to distinguish between the tribal and the non-tribal way of life. Like the native (formerly called "red") Indians of North America and the aborigines of Australia, some tribes in India (such as the Todas of Nilgiri Hills) have become mere show-pieces, for the sole purpose of attracting foreign tourists. Other tribes like the Halakki Gowdas of the Indian west-coast have adapted themselves to agriculture. Some other tribes have taken to mining and hence it is almost impossible to find pure tribals who have remained unchanged for centuries.

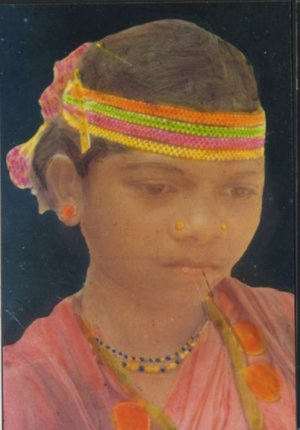

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Tribal Girl of Bastar

Photograph hand-colored by Kamat

Fortunately for historians, anthropologists and sociologists, there are still a few tribes in the Bastar district of the state of Madhya Pradesh, which are totally unaffected by any developmental program, and therefore are used here as a model for the study of "Women in Tribal Societies." These tribes are restricted to the Abujamara (see also: Abujamara from stories of Bastar travel) area of the district, which is totally cut off from the rest of the country by mountains, hills, rivers, springs, ever-green forests and a total lack of roads and communications. The authors visited this area and studied these tribes for a year on a fellowship from the Karnataka State Literary Academy. This paper is therefore based more on personal experiences and anecdotes than on published research papers, and this has resulted in a reduced number of formal references.

Tribals of Bastar District

These tribals are mostly confined to Narayanpur tahsil (county) where their population is as low as twentypeople per square kilometer (1975)! These tribes had earlier been classified among Gonds but anthropologists recently found them very distinct from the Gonds and gave them the names "Hill Marias", "Buffalo-horn Maria" and "Murias", based on their geographical distribution, attire and costumes employed in their dances. However they are locally known by names such as "Meta Koitor," "Dandami Maria" etc. They live in small villages consisting of not more than twenty-thirty houses. Their everyday activities are so well coordinated and inter-linked that one is tempted to view the entire village as a super-family. Irrespective of one's gender, every person has a vital role to play in the welfare of the community.

A house-wife is the nucleus of domestic activity. She rises early in the morning, fetches water from a distant spring, prepares a breakfast of "paje" (pottage) for the family, brews "landra" (a liquor) for the adults, cleans the house, cooks the other meals, accompanies her husband to the forest, and gathers fruits, leaves and firewood while the husband hunts. During the monsoon season, she assists in all agricultural activity and this includes hard labor. In a competition she could win an award for speed and distance-walking! She can cover forty to fifty kilometers in a day, can carry a heavy-load on her head through difficult mountains and can go without food for an entire day. How many of us can even think of choosing such a life?

Compared to modern women a tribal woman has very little wealth of her own or of her family. She has just a piece of coarse cloth to cover her womanhood. She is very fond of ornaments, yet has just one or two strings of red, blue or white beads. In addition, she may have some bangles, earrings and necklaces made of cheap metal. That materialistic comforts and riches are not the indices of happiness is well illustrated by the tribal woman. She is always very cheerful and light-hearted, often laughing and joking with members of her family or with the neighbors. She is truthful and honest. She never denies any offense she might have committed and willingly faces the consequences. These are some of the sterling qualities, we the modern women and men have to learn from our tribal sisters. It is true that the tribal woman avoids outsiders, but once she gets over her natural shyness, she is extremely frank and communicative. Considering her utter poverty, and her constant struggle to maintain the barest minimum standard of life, her light-heartedness is amazing.

Women-libbers of the outside world may feel ashamed if they come to know how tribal women have acquired a dominant role of partnership in married life. The tribal woman fondles her man like she would a child, loves him like a paramour (lover), keeps him company like a companion would and works with him like an equal partner. While she will do everything for him, she will never be his subordinate. She has gained this status by sheer hard work and not by being demanding. There is nothing she will not or cannot do. She even attends to the funerals of her near and dear ones, something so called 'refined' Hindus do not allow for a woman. The tribal woman also assists in erecting a memorial for the dead.

The birth of a son is not a special cause for joy (as elsewhere in India), as boys and girls are considered equal to the tribals. The modern mother, who undergoes an abortion after learning from latest clinical techniques, that her fetus is that of a girl, should learn from her tribal sister, to accept the children of either gender, as a gift of God Almighty. A tribal woman declares her pregnancy with pride and does not welcome her husband till she is willing to conceive again. Delivery is without the assistance of a midwife and mother herself cuts the umbilical chord. The mother nurses the baby with her milk, carries it everywhere in a piece of old cloth hanging from her shoulder. She puts her child to sleep in a bamboo cradle. Older sisters attend to their younger siblings. The young girls are of fair color, graceful and pretty, but as they grow older this gloss diminishes because of frequent child bearing, long journeys to markets and fairs, and heavy domestic and field labor. The tribal woman does not fight the aging process but becomes a grandmother gracefully.

The Institution of Ghotul

Tribal houses are too small to accommodate a large family. Therefore, they have adapted a special institution called "Ghotul" to solve their accommodation problem. The Ghotuls are predominantly found among Murias and to a lesser extent among Marias. Boys and girls six years of age are entitled to membership. The female workers of the Ghotul are known as "Motiyaris" and they are assigned important administrative duties at the Ghotul. They are responsible for the general cleanliness of the building and premises, the punctual arrival of members, the taking of the attendance, the supervision of sitting arrangements, and the assurance of liberal supply of fire wood, mustard oil, tobacco and landra. Each girl has to attend to a male member of the Ghotul. If he is extremely tired after a day's work, she massages his body and applies oil. If the boy is pleased, he presents her with a wooden comb and perhaps a plum.

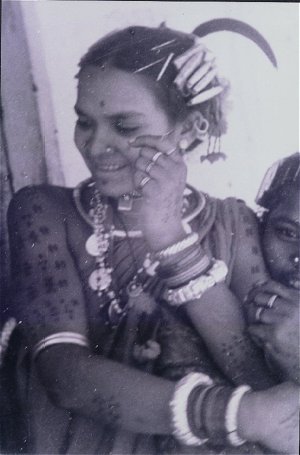

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Tribal Beauty

Girl decorated with commonly available beads and coins at the tribal educational institution of Ghotul

When activities for the night commence, the girls have to intermingle with the boys and distribute themselves around the fire. Together they gossip or make fun of each other. This is followed by more serious discussions, group singing, playing of musical instruments and dancing. When it is time to retire for the day the girls share beds with boys. This is perhaps the tribal way to inculcate the habit of community living amongst youngsters! These tribals have perfected the art of co-existence from time-immemorial whereas the most advanced countries such as Sweden and U.S.A. have had to introduce such a system of co-education only in this century. Nobody should be under the impression that Ghotul life is permissively vulgar or promiscuous. Residents are expected to play the game of love by strictly adhering to all the rules and regulations. It is our belief that the mothers train their daughters to the extent they can go at the Ghotuls. Any lapse on anybody's part attracts very severe punishment from the authorities. Therefore, premarital pregnancies are very rare. If it does happen, then the girl names the father and a wedding is quickly arranged.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Savage or Civilized?

A very fashionable student at the tribal co-ed institution of Ghotul

Marriage is a very serious matter for the tribals. Each group is identified by a clan and a set of clan-gods. No marriages are permitted within a given clan, as all the members of a clan are considered to be brothers and sisters ("Dada-bhai."). When a woman marries outside her clan, she is considered a part of her husband's clan. A consanguineous marriage across-clans is encouraged as the couple in question belongs to different clans and therefore considered to be "Ako-mama". A girl thus has the right to select her father's sister's son as her life partner. Similarly, a girl can marry her maternal uncle. A woman has a free hand to select her groom and is never compelled to marry a man against her choice. Child marriage is not permissible and pre-puberty marriages are quite unheard of.

Tribal brides are in great demand and therefore the groom's party has to pay the "bridal price" which is determined on the basis of the bride's age, socio-economical status of both parties. In the event the prospective son-in-law is not in a position to bear such an expense then he has to work in the bride's house for a number of years before the wedding is arranged. The bridal price is not paid in cash but in kind, such as grains, fowls, pigs and wines, to meet the marriage expenses and host a grand dinner and a drinking bout that follows the wedding. All the members of the village Ghotul are invited to participate in the wedding by singing, dancing and drinking. If at any time in the past, the groom happened to misbehave with any of the Motiyaris then the entire female fraternity boycotts the wedding. This is a great deterrent, because it is very hard to think of a wedding without the cheering and loud laughing of Motiyaris.

Each tribe follows its own custom after the wedding. The bride may go to her in-laws' house, or the groom may join the bridal family and in some cases the couple may start a household of their own. All the members of the groom's family, especially the bride's brothers-in-law, treat her with great respect and kindness. A tribal woman faces sickness, accidents, calamities and even death of near ones with calm and resolve. In the event the husband prematurely dies, it is his younger brother who has the first right to marry her. The bereaved widow also has an equal right to refuse him and marry anyone she takes fancy to. But no one is allowed to have more than one wife, and a widower or a divorcee is not allowed to marry a virgin. A widow's new husband has to pay the bridal price to her former husband's family.

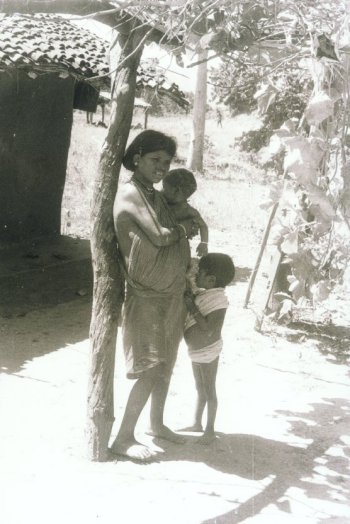

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Waiting for the Man of the Household

A tribal family waits for the father to return from forest, village of Chote Dongar, 1976

At times the tribals also run into marital problems. If a husband turns out to be brutal, crude, insane, impotent, unfaithful, criminal or diseased, then the wife has every right to complain about him to the tribal head Manji (or Patel). He in turn assembles his advisory council and gives an opportunity to the couple to plead their cases. If the council is convinced of the husband's guilt, the wife is allowed to get a separation and marry anybody she chooses. In some instances the former husband has tried to disturb the wife's new household and in the scuffle that ensued the former husband has been killed by the wife. In such an event the council has no hesitation in pardoning them all. What a down-to-the-earth system of justice this is! Of course, after the tribal court's decision to acquit, civilized people outside have sometimes dragged them to criminal courts where they were found guilty and imprisoned for life!

In tribal society women are not treated as inferior or second class citizens. Although they are on par with the men, they complement rather than compete with each other. This status of the tribal women has existed from ancient times, as can be seen from rock paintings found in the state. These paintings were executed as early as five to fifty centuries before the birth of Christ. Most of these paintings represent hunting scenes, fighting sequences, animal sacrifices, rituals to ward off evil spirits and so on, and hence women do not find much of a place in them. But in the scenes that depict every day life, women are shown to be involved in food gathering, basket weaving, singing and dancing. Pregnant women, women giving birth, and nursing mothers are also depicted. This perhaps indicates that the women represented fertility, motherhood and were the progenitors of the tribe. This special status for women might have given rise to the mother-goddess cult. Even today most of the tribals of the area are the worshippers of the goddess Danteshwari.

It seems as though inequality among modern men and women is a curse of the civilized world and the women's fight for equal right with men is the luxury of educated, city bred women, and wage earning socialites. These modern women are at cross roads; while enjoying their special status, they also want equal rights! All their problems do not arise out of inequality alone; a good number of men are self-seekers and exploiters. In the guise of a son, husband, father, and custodian, some men attempt to corner all the benefits that may be derived from the fair sex. This may be in the form of dowry, property, earnings, physical comforts etc. "Women in Tribal Society" gives some insight into how some of the modern woman's problems can be solved.

Tribal women themselves are increasingly subjected to the stress associated with the developmental activities. The tribal women were free from sexually transmitted diseases as they have healthy sex. But when the Bhiladela iron ore project commenced a large number of tribal men and women rushed to the construction site in search of a better way of life. Unfortunately, the women became the victims of lust and rape and hence had to take to prostitution to earn their living. Even those who were employed as cooks and maid-servants in the houses of the officers were used as mistresses by them. If and when they conceived, the employers did not hesitate for a moment to caste aspirations on their character and drove them out of the house. In this way, men without any character became the judges of morality of the tribal women. If something is not urgently done to save these women from the clutches of these unscrupulous men then a day will come when there will be nothing to talk about the "Women in Tribal Societies".

___________________________

Opinions are that of the authors only.

References

- Elwin, Verrier: Leaves From the Jungle: Life in a Gond Village, Oxford University Press, 1936

- Elwin, Verrier.: The tribal world of Verrier Elwin; an autobiography., Oxford University Press., 1964