Vocational Education

In ancient and medieval India, the caste determined a particular vocation. Each person of a particular caste followed his or her family profession known as kulada kasabu or kulavidya. Sculptors, painters, weavers goldsmiths, copper and brass smiths, gudigars (artisans), temple builders, physicians, purohits (priests), astrologers, one and all followed their hereditary professions. The young were exposed to these skills from their childhood and with intensive training became masters in their particular family-art or craft. Cave temples of Ajanta, Ellora, Badami, Bahubali statue of Shravanabelagola, and temples of Belur and Halebidu speak volumes of the superb knowledge these master- craftsmen received and exhibited. Similar is the case of skillful mastery of panchaloha (alloy of five metals) images visible in innumerable temples of south India. From sandalwood carving and ivory carving to Bidari work, from Ilkal saris to gold and silver filigree work on silk and brocades, Karnataka has made its name through centuries. One is wonderstruck that with no mechanical help or machines such masterpieces big and small could be shaped out of sheer manual skill.

In addition to the social milieu, it was with deep dedication and devotion to the God Almighty that these crafts and skills were practiced. They received very little in the form of remuneration in return. It was cash, kind or land after completion of assignment. But they were a contented lot. The meager returns did not come in the way of their attaining excellence. Most of these masters are anonymous but have left a legacy, which leaves generation after generation wondering at their extraordinary skills.

![]()

Education for crafts and commerce

Although divided into the four varnas (castes), the medieval society in Karnataka was not as rigid as described in the Dharmasastras. The shudras freely entered the army. This naturally led to their getting training in arms and warfare. Devala Smriti injunctions quoted in Mitakshara, a local commentary, speaks of the common practice that the shudra community was to engage in agriculture, rearing cattle, sale of commodities, drawing, painting, dancing, and singing besides serving the twice-born. Hence little difference is observed among the professions, which the Shudras, Kshtriyas, and Vaishyas followed in everyday life.

In all arts and crafts, education started early, mostly at the age of five years. Schooling was at the home of the craftsman itself and the teacher was either the father or the head of the family. On an auspicious day the boy had holy bath, new clothes and he was made to sit on a wooden seat. Puja was performed and obeisance made to Ganesha or Saraswati or both, who are presiding deities of education. Sand was spread on the ground and letters "Sri" and "Siddham namah" (a legacy of Buddhist times) were written on the sand and the boy was to copy it and the initiation of the boy-craftsman started. After learning letters the child was slowly introduced to draw lines, figures and geometrical designs. The children slowly learnt copying, sketching, and rough carvings. Later simple floral designs and outlines of animals and figures were taught. Under the direct supervision of elder brother or father, a new lesson was taught everyday, which was practiced or etched. Slowly the youngsters started helping the father and his team in getting the tools like chisel, bodkin, trowel, and thread (measuring tape) ready and help in sculpting, carving, and designing. In the evening sutras (treatises) pertaining to shilpashāstra (science of sculpture) were taught by heart, which the boys were supposed to master at the end of the apprenticeship.

Particular guilds existed for each artisan or craftsman group, which provided specialized professional or technical know-how. These were known as gottalis or gondanas equivalent to srenis or nigamas of North India. Each city or large town had particular keri or suburb, sometime street of such gottalis. Kannada kavyas (classics) speak of gottalis of different crafts. After the training or apprenticeship, which lasted for a minimum of seven years, the trained youngster was free to work on his own or act as an assistant to Oja (master craftsman) or Acharya.

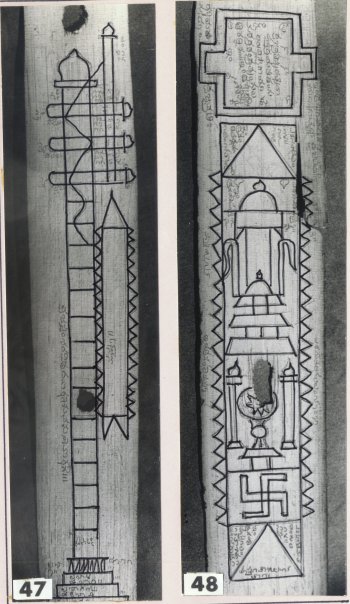

Whether it was a huge idol or a full-fledged temple, the architect and chief sculptor were chosen by the patron, and on an auspicious day, they were offered fruit, betel and symbolic gold which signified a contract. The master sculptor and his team used to undertake the assignment from that day. The master was adept at judging the quality of the stone, specific requirement of plinth, pillars, and pavilion. Blueprint was drawn on huge boards and mini-sketches on palm leaves to help the students. Such sketches of pillars and flagstaff are available in palm-leaf books today, even after seven or eight centuries (see pictures 47 and 48).

K.L.Kamat

Blue-print of Sculptures on Palm-leaf

Picture shows architectural drawings done on a palm-leaf, perhaps from a sculpting school

The task of temple building was duly divided among the teammates as per their capacity. The project used to be time bound and when the work could not be completed, the team worked late into the night under the "hilal" light (torch made with palm leaves). The day of installation of the deity was a great moment in the life of the artisans and craftsmen and touchstone of their unstinted labor. The team was duly honored and paid in the form of cash or land and finally they considered fulfillment in the dedication of their masterpiece—the temple, to the principal deity of the patron who undertook the construction. Their involvement and dedication to the cause was total. This is perhaps the reason why much of the medieval artists have not left their name behind in writing, to claim intellectual ownership of their artwork.

Legendary sculptor Jakanachari is a household name in Karnataka. The great guru, we are told, who built innumerable temples had to acknowledge defeat from his own son, Dankana. Though there is no historical evidence to prove this story, Jakana represented a school of sculpture which was a beautiful blend of Dravida or southern and Vesara or western styles, which flowered during twelfth to fourteenth century. Till date, we are in the dark about the sculptors who carved the great temple of Kailasa at Ellora or the statue of Gommateswara at Shravanabelagola. Only a few names Mabana, Nagoj, Devoja, Mallitamma etc. who have carved the bracket images and floral designs in Halebidu and Belur temples have left their names, in beautiful calligraphy. One Poysalachari calls himself learned in the science of sculpture but a disciple of those who handled chisel (uli) and thread (balli) in all humility. Perhaps, he was a royal sculptor.

K.L.Kamat

Shanmugam (Karthikeya) on a peacock

Note that the name of the sculptor Mab-sanmab has been carved at the base of the panel

Training in painting was not very different from training in sculpting. In fact, mastery in drawing and sketching was the basis for learning other fine arts involving manual skill. In Buddhist system of education mastering one art (shilpa) was compulsory for Bhikkus. Painting portraits and frescos were quite popular and kings and queens, ganikas (courtesans), princes, and nobles as also commoners practiced painting. Children after initiation were taught to draw lines, straight and curved, eye and hand measurements, and memory drawing. Symbols and geometrical patterns were introduced and stories from Ramayana, Mahabharata and other classics were narrated along with illustrations. Youngsters were taught the theory of natural colors and color combinations as also the methods of obtaining them from red ochre, coal, various minerals, leaves, flowers and bark. Coconut shells of various sizes were used as bowls for keeping colors. The boys also learnt to prepare brushes of various sizes. Brushes of hair of boars, camels and sheep were used for rough work. Hair from squirrel's tail and calf's ears made brushes for finest and delicate painting. This hair was tied with silken thread to a stick and the required brushes of various sizes were prepared. At the elementary stage, sand and cloth blackboard (kadata) were used for drawing and later canvas and charcoal helped the students. Anatomy and pratimālakshana (iconography) followed at advanced stage.

Before the paper made its appearance on Indian scene, palm leaves were used for illustrations. Some childish attempts to draw figures of animals have survived, and it is difficult to determine (see pictures 52 to 55) which animals, these figures represent!

The guru or teacher was to determine the period of training (kālam kritvā sunischitam) and arranged for boarding and lodging of the students1.The system of ancient Gurukula continued in a way with certain arts and crafts. Expenses were borne from the sale of ware completed by the guru with the help of team of student assistants. An ideal guru was not supposed to get his personal work done by them (na cha anyat kārayet karma). The king was directed to punish master craftsmen, who at time exploited students. After completion of the course, tours were undertaken to holy places where temples of unique craftsmanship existed, and students received first-hand information of splendid work. Due to rain, humid climate, harsh wind, burning sun and apathy of commoners most of our masterpieces are lost. Few existing remnants at Hampi, Lepakshi, Shravanabelagola, Mysore, Seebi (a.k.a. Sibi), Mysore and Srirangapattana still bear witness to the bygone glory of Karnataka paintings.

Konkani artists in the region of Goa developed the monochrome designing of red ochre on whitewashed walls known as the Kavi art centuries ago. After the Portuguese occupation of Goa when forced conversions started taking place in the 16th century, several Hindu families migrated to Karnataka, and with them came the Kavi artists who where associated with temple building activities. Temples built in the Karnataka region by these immigrants especially in North and South Kanara districts bear the stamp of this monochrome art of fresco painting. Like other painters of wall paintings, these knew sutras (formulas) of chitra karma or painting, by heart and were conversant with anecdotes from the Ramayana, the Bhagavata and the Shivapuranas2. Required sequences from these works were drawn on paper and transferred on whitewashed walls. Later red ochre paint, (which is available in plenty in stone and earth form in the region), mixed with chunam (lime) of seashells was applied to the walls. With sharp bodkins, lines, designs and figures were drawn on plastered red-ochre. Additional plaster was skillfully removed. The bright deep red paintings on whitewashed walls looked very attractive. It was a common practice among the gentry to get adorned mansions and prayer halls besides temples with Kavi paintings (see: Kavi Art), and many well-to-do families got portraits of their elders made in their houses, along with those of deities and saints. At some places names of deities are written in Kannada and Devanagari scripts below such pictures. Many pictures, which survived for centuries, were destroyed when temples and old houses got renovated and cement and distemper began to rule.

![]()

Metal crafts

There was great demand for copperware, brassware, bronze and silverware along with panchaloha idols in the days when stainless steel was unknown. Each city and town had smithy of such varied wares. The residences of these craftsmen were like mini-factories. Elders, adults, children, at times women, were busy molding, casting, melting various metals, and polishing. Theirs was indeed a very hard life, which involved long hours by burning fire and smithy. They also had to undertake journeys to sell their finished goods. Village shanties and annual fairs provided good opportunity for their wares. Most of these metal crafts, which produced essential household goods, like pots, plates, glasses, and vessels of various shapes for various chores are now lost forever. Only panchaloha images in some temples and basadis remain as examples of delicate craftsmanship of our elders. A few museums and art centers are exhibiting replicas of art pieces of bygone days.

![]()

Yakshagana and Huvina-kolu

Yakshagana or folk theater of South Kanara has received worldwide attention due to tireless efforts of late Dr. Shivaram Karanth and also dedicated study of American teacher Dr. Martha Ashton. There are families of several generations who studied this ancient art, wrote prasangas (theme anecdotes), sang, danced, narrated and taught as well. Besides family members, the interested male youngsters also joined classes at the residences of respective teachers. There were touring troupes of professionals. They enacted female roles till their voices cracked and appearance started changing to manhood. They helped in carrying costume and make-up boxes from one place to another, fixing up and decorating the stage, and did many minor roles rising to occasion. They also performed in the beginning of a show. They enacted and prepared impromptu sequences, till the main characters came fully dressed and took over the stage. The prologues by the talented kids and youngsters were greatly relished by the audience. The prolonged rainy season in coastal Karnataka helped the Yakshagana artists to stay at their village home and practice new episodes and dance plays and brush up their art.

The students pursued the study of Sanskrit and Kannada classics that they had started at local mathas of Aigal (teacher). Talented among them and those blessed with resonant voice made good bhagavatas or narrators, who are the backbone of a Yakshagana dance play. The bhagavatas were supposed to know of elements of Bharatanatyashastra as well.

Poet Payanavarni's Jnānachandra Charite (16th century C.E.) mentions children singing choupadis (four liners) holding flower stick during the Mahanavami festival. In olden days Yakshagana anecdotes were taught to children in Aigala mathas in South Kanara District as part of the curriculum. By the time the matha education was over, the children knew several Yakshagana prasangas by heart.

Huvinakolu songs were sung by the trained students in teams of two or four in selected households before the elders and the head of the family, to the accompaniment of maddale (drum) and shruti and guided by the bhagavata. The songs, choupadis were of the nature of community welfare. Seeking blessings of the Almighty, of the master of the house, wishing health, wealth and welfare of the family, or greeting of the season, formed the content of the songs. The underlying idea was to exhibit the talent of youngsters and their training and to earn gurudakshina (fee to the teacher) in cash or in kind through goodwill.

After initial prayer and goodwill songs, parts of Yakshagana on Chandrahasa or Dhruva (in which child is the hero) were performed till the main performers came on the scene. The delighted householder donated presents liberally in cash or kind to the performers.

Musical instruction

By the 10th century, Karnataka had evolved its own school of music, dance, and drama imbibing all the tenets of Bharata's "Natyashastra". This is quite evident from poet Pampa's famous description of Nilanjane's dance sequence in his Adipurana. Since music and dance were the most popular entertainment, they developed into various forms to cater to different sections of the society. Manasollasa has devoted a very long chapter containing 950 verses to music, dance, and drama. It involves scientific classification of ragas, mode of rendering them, description of various instruments, blowing and percussion, manufacturing and playing them, art of dance, qualifications of vocalists instrumentalists and dancers. Thematic dances and operas were known. Bhulokamalla, the author was not only a great musicologist but seems to have been a good musician as well. We may conclude that by 12th century, Karnataka was at its peak in these arts. This fact is attested by various dance postures in temple sculptures and description in kavyas. Methodology in music, given in Manasollasa was followed by one and all in the following centuries.

Contribution of Purandaradasa (c. 16th century) in popularizing music among the masses through simple rhythmic compositions is unparalleled. He composed hundreds (tradition ascribes thousands of songs to him: since they have come down to us through oral method, there is likelihood that many might have been lost) of compositions. He included anecdotes, legends, moral lessons and virtues of pious life. There are songs for all occasions. Songs of prayers, and songs for bathing, feeding decorating the deity, lullabies, songs of household chores and purely devotional ones. Even beggars, illiterate farmers and housewives could render them with feeling, and depict their own nuances. The songs could be set to tune to any instruments including single string (ektari), tanpura, and kolata (play with sticks). Purandaradasa's compositions on Ganapati, known as pillari geete, in sarala varase, janti varase and alankara are sung in all the four southern states irrespective of language differences at the initial stage. It is no surprise that he is known as the father of Karnataka (a.k.a. Carnatic) music.

It is generally believed that Tyagaraja (c.18th century) was greatly influenced by Purandaradasa. Since Vijayanagara times, Andhra-Karnataka had common cultural heritage and music was the strongest link. Kannada compositions were common in Andhra and Tamilnadu and Telugu compositions are sung in all the states of south India.

Medicine

Medicine was known as Ayurveda and studied in certain families for generations. Outdoor activities i.e. wanderings in jungles and mountains was compulsory for would-be-physicians. They were supposed to know not only each and every herb, their medicinal worth, but also flowers, roots, leaves and barks of trees. Collecting these, processing, drying and preserving was equally important. Rare species were obtained from Himalayas, down to mountains of Kerala. A village pandit or physician was very important and much sought-after-person, who catered to all the health needs of village community. No fee was charged though the cured grateful people tried to repay in kind3. One Parahita, taught all vidyas of veda and ayurveda to his students and thereby attained life's fulfillment says an inscription4. Students of Ayuruveda had to study the works of Charaka and Sushruta in Sanskrit and commentaries thereon. Physicians were supposed to be above caste and creed and we find many well-known physicians in the Shudra community. One Nanjamma of Gangadikar community is mentioned in an inscription, who administered medicine to smallpox without differentiating among the brahmins, the kshatriyas and the shudras5. Many housewives who learnt this science through their mothers were versatile in preparing home-medicines by growing medicinal herbs in kitchen-gardens and served the society in their own way: A rare sculpture in Bhatkal temple depicts an elderly woman physician examining nādi (pulse) of a young girl.

Education of trading class

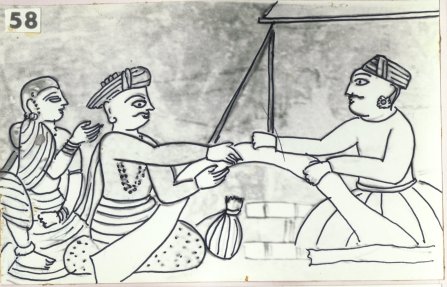

A good deal of talent, adventure, and persistence were required for traders to sell the goods. They received intensive professional training besides the fundamentals of reading, writing, and the arithmetic. They had to learn several languages, art of communicating, courteous and pleasing ways, besides efficient and quick counting and accounting. This training helped them to undertake journey to distant countries and climes. They were adept in ways of travel and knew the geography of several regions. The father or the elder of the family taught tricks of trade. Branches of various guilds, which existed in big cities and important trade routes, helped in arranging food and lodging to individual traders and caravans. We have interesting frescos in the matha at Shravanabelagola, which depict sale of cloth (see picture no. 58) and grocery (see picture No.59) wherein the petty shopkeepers try to cheat but are caught and admonished by the wary customers.

K.L.Kamat

Medieval Cloth Merchant

Detail from a mural in Shravanabelagola

K.L.Kamat

Medieval Grocer

Detail from a temple mural depicts a grocer with a balance

Trans-oceanic trade was brisk during Chalukyan and Rashtrakuta reign. Kalyana and Surparaka (now both in Maharashtra) were famous international ports. Trade with Persia, Arab countries, Greece, and Rome took place on a large scale as also with Suvarnadvipa (Indonesia) and China in the east6. The trading class known as Ayyavoleya Ainuru, and guilds of Vira bananju and Nanadesis were powerful and controlled the trade and commerce of the entire subcontinent and beyond the seas. They were expert in norms of voyage, import and export polices of various countries, and coinage. With the arrival of the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English, some Konkani traders in Karnataka lost no time in mastering their languages. They acted as interpreters to their rulers like those of Keladi, Kerala, Maharashtra. Names like Vitthala Mallya, Ganesha Mallya, Rama Kamath, occupy important place in the annals of coastal trade.

Artists and craftsmen received better and organized patronage under the Bahamani rulers. "Karkhanas" or factories made their appearance. Handicraft centers were attached to palaces. Spinning, weaving, printing, embroidery, jewelry, in-lay work, painting, writing and illustrating on paper took place on a large scale. Bidar and Bijapur became important trade emporiums, and there was huge international demand for Indian textiles, jewelry and embroidered goods, and carpets. Bahamani (1347-1527 C.E.) and Adil Shahi (1489-1686 C.E.) rulers got skilled craftsmen from Shiraz, Isphahan and Damascus and got the locals trained in lacquer work, metal and inlay work, Kalamkari and papier-mâché. Later these attained indigenous art form and continue to draw international attention. Tippu Sultan (1782-1799 C.E.) gave existing Karkhanas fresh boost by introduing modern technology. Manufacture of sugar, glass, quality cloth, paper, and cutlery were started in Karnataka. Experts from Bengal, China and France arrived at Tippu's invitation. Mulberry-farming started and some very fine weavers came from Tamilnadu. Tippu Sultan could very well be credited as a pioneer in "Karkhana revolution" not only in Karnataka but in the whole of India as well7!

Most of the arts and crafts like carpentry, tanning, extracting oil, dyeing, and coir, matting etc. were home based, and catered to the local needs. Women and children received all essential training in respective crafts in their families, early in life and helped the contemporary society to be self-reliant.

![]()

References

- P. V. Kane. The History of Dharmasastra, Vol. II (1), p. 364-365.

- Krishnanand Kamat. Konkanyali Kavikala, Mangalore (Konkani),2000, p. 118.

- Sudarsana (Dr. T. M. A. Pai Felicitation Volume), p. 365.

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. V. no. 8-11,

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. VI (new), p. 23.

- A. N. Upadhye (Ed.) Kuvalayamala of Udyotanasuri, p. 73.

- Suryanath U. Kamath. Ed. Karanataka State Gazetteer I. p. 889.