Education of Women

It is an established fact that there was no gender discrimination in Vedic age in imparting education. Boys and girls alike had initiation (upanayana) ceremony before they started their studies in a gurukula or hermitage. But only a few girls must have taken to austerities of hard life and in depth study of vedic lore. Majority of girls as in any clime and country preferred cozy home-life, cultivated various arts and crafts and became good housewives. These were known as sadyövadhus.

Among those girls who took to

serious study of God-realization in a gurukula, some excelled in all

existing ways of learning and especially in disputations regarding the nature of

Brahman. They are known as brahmavādinis, and remembered as

visionaries and composers of mantras. Twenty-seven brahmavādinis are

hind mentioned in vedic literature. These women dedicated themselves to

spiritual life, preformed vedic rituals, guided the householders in the

religious matters, and led the life of the rishis (ascetic). Though we do

not find brahmavādinis in later centuries, female ascetics continued

their contribution in helping the laity in all spiritual matters. We find female

ascetics of all religious sects, Buddhist, Jaina, Shākta, Vaishnava, Shaiva,

Gānāpatya and Virashaiva mentioned in inscriptions and classics of

later times.

One Gangikabbe presided over a matha

at Potturu, received a grant from Chalukyan princess, Akkadevi in 1065 C. E. and

ensured welfare and proper education of inmates of the matha. She is showered

with all customary titles bestowed on male ascetics of the highest order.

Another was a kshetrasanyāsi or ascetic of the holy place and

respected by Yadava rulers as head of Mahanubhava sect. But the outstanding

learned lady of the times appears to be Savinirmadi, whose portrait in stone is

fortunately available to us.

Savinirmadi's memorial of about 10th century C.E., shows a young woman seated on a coach in preaching posture. This indicates that she was a preceptor of eminence. The figure is neatly dressed in a sari with flowing pleats. Her thick hair is arranged in a matted top-bun, befitting a sage or tapasvi. In the left-hand, she is holding a palm-leaf book with Kannada letters…"Shri Hari (ra) Siddhi" with one finger carved as concealing the letter "ra" or "ri." Above the sculpture, two lines are inscribed in the Kannada characters of 10th century. It states that Savinirmadi, the daughter of Nagarjunayya and Nandigeyabbe was learned in all the shāstras1 (see picture no.62).

Savinirmadi, a commoner seems to have been a unique scholar, as the people of the region deemed it fit to erect a stone memorial. Only the names of her parents are mentioned leading one to believe that she did not marry. Considering the milieu, this is puzzling. If she were a nun, details of her religious order would have been mentioned leading one to believe that she did not marry. Neither is the short engraving a part of royal decree, which is the usual norm. This leaves room to the assumption that Savinirmadi opted to remain single, dedicating her life to the study of scriptures, and interpreting them to the people of locality. Those grateful people must have erected this stone in her memory, perhaps on her untimely death.

![]()

Eductaion of Housewives

Vatsyayana (1st century C.E ?.) has listed several household chores, arts and crafts a housewife had to

supervise. These included gardening, growing medicinal herbs, spinning, weaving,

classification of grains, maintenance of granary, care of domesticated animals,

housekeeping, accounting, reading and writing. Administering medicines, physical

exercises (vyāyāmiki) painting, and tailoring besides cooking

were the topics a housewife was to know.

It is obvious that women of

Vatsyayana's time were expected to be adept in household chores and

cultivation of arts and crafts as well. He further suggests that a musician, a

princess or daughters of nobles could control the household by cultivating

various arts and subjects. In case of separation, death or a long journey, such

ladies could spend time by learning fine arts, he advised.

Again from Vatsyayana we learn

that experienced nurses, confidantes, old maids, nuns, and even aunts taught

various subjects to young girls. This attests the fact that India boasts of a

long and sound system of domestic system of education, which has come down to

two millennia. Karnataka was no exception, and we have references in old Kannada

classics of nuns, nurses and old maids teaching princesses and daughters of

nobles. At times father took active interest to educate girls.

ädipurāna, the Jaina classic

of Pampa provides glimpses of early education for girls. Vrishabhadeva, the

first teerthankara one day

sent for his two daughters Brahmi and Sundari thinking to educate them. He was

convinced that education would add to their virtues. He seated them on his lap

and wrote the letters "Siddham Namah" (a legacy of ancient times) for Brahmi.

To Sundari he taught arithmetic. Then he proceeded with formation of words,

figures of speech, literature and all arts (samastakalāsamuha) one

by one2. They both were perhaps five year old and this was the age

considered fit enough for schooling boys and girls in ancient times.

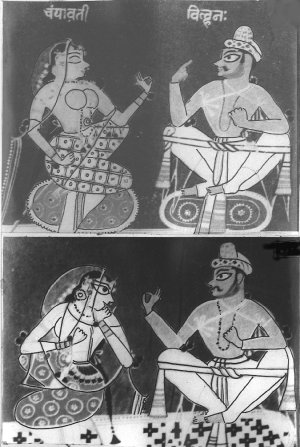

Men teachers were employed to teach the princess. Bilhana was a court-poet of Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI who ruled from 1076 to 1127 C.E. He hailed from Kashmir and is credited with Chorapanchāshikha a short work of fifty verses. Many scholars believe it is based on his personal experience. The king, his earlier patron, thought the brilliant poet would make a good teacher to his beloved daughter Champavati. But as per existing norms he dared not leave both of them alone for hours together. Hence the princess was briefed to keep her eyes closed during the lessons given to understand that the poet was suffering from leprosy. The poet was told that the princess was born blind. The lessons continued for a while. But the cat was out of the bag shortly. The guru slowly won over the disciple by pleasant conversation and love lyrics! Both fell in love and when the king came to know about it, he ordered the execution of the poet forthwith. When Bilhana was being led to the place of execution, verses broke out spontaneously and the people who had lined on both sides of the road listened and broke into tears. The anger turned to compassion; the king let Bilhana go free and married off his daughter to him3. A 14th century manuscript of this love-lyric depicts (see picture no.s 63 and 64) stages of lessons taught by this poet to the student with eyes open and eyes shut!

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Romancing the Teacher

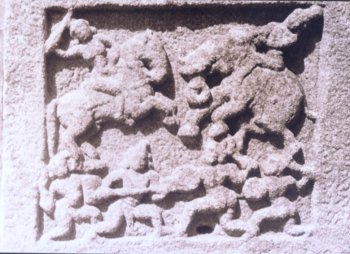

In the higher strata, girls were taught state-craft, horse and elephant riding and wielding of various weapons. We have a rare sculptural representation of Saviyabe, falling in the battlefield fighting to save her husband.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Horse-mounted Saviyabbe Avanging her Husband's Death

A 10th century memorial depicts a woman killing a elephant mounted enemy

Princess Akkadevi, governor of Banavasi province (1024-1068 C.E.) defeated the rebellious chieftain of Gokage, when her military skills shone and won her the title of Ranabhairavi (goddess of battlefield.) The tradition continued till the 17th century. Mallamma, daughter of the chieftain of Sonda was taught martial craft along with her brother Sadashiva Nayaka. This included horse riding and wielding of various weapons. (Appendix A). She put to good use this initial training by coaching two thousand women of her principality who gave a tough time to the troops of Shivaji when her place was invaded.

![]()

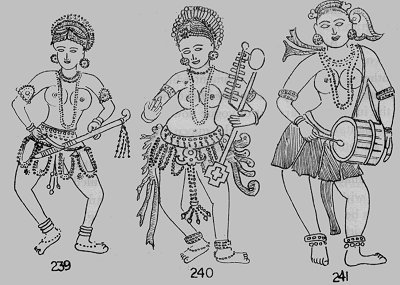

Mode of Teaching Dance and Music

There were halls for instructing females, which were known as kannemāda in palaces and mansions. Music, dance, drama, and painting were taught also by male members as confirmed by Kannada classics4. We have sculptural and pictographic evidence regarding such lessons (see picture no. 67). Female teachers carefully watched the footwork (see picture no. 66) and students spent long hours rehearsing (see picture no. 68).

© K. L. Kamat

Picture 67: Teacher Examines Homework

© K. L. Kamat

Picture 68: Girl Engaged in Self-study

Domingo Paes had occasion to visit

such a kannemāda and has left good description. He saw a long hall

with pillars of sculptures of dance poses on all sides. Some showed positions at

the end of a dance-sequence to remind the students in case they forgot. There

was also a painted recess where women could cling with hands, stretch, and

loosen their bodies and legs. This helped them to keep their bodies supple and

graceful5. Paes also saw the golden image of a girl of twelve years

in a dancing pose. This was the age when dancing lessons started for girls as

per Shivatattvaratnakara, an anthology of 17th century. The right age

for a performing dancer was up to thirty years6.

A female dancer of olden times had to be versatile. She had to learn music, acting, recitation from classics and narration as well as composing verses.

![]()

Visual Education

In the palace of Krishnadevaraya (1519-1529 C.E.), Domingo

Paes had noticed painted walls in the interior parts of the zenana. There

were pictures of peoples of different countries and their ways of life, who

frequented Vijayanagara down to Portuguese. This enabled the king's wives

"to understand the manner in which each lived in his own country, even to the

blind and the beggar." 7 This system of painting walls to teach

palace women history, geography and classics was common. Mysore king Kanthirava

Narasaraja's inner apartments had episodes from Ramayana, Mahabharata and

Bhagavata. There were life-size sculptures of swans, peacocks, elephants, bison,

and tigers in forest scenes8.

Bedrooms had painting and sculptures of erotic themes on the walls as described in Kamasutra. These were obviously to impart sex-education to young couples. The courtesans and the rich also got certain rooms in their residences painted with such scenes along with those from classics, animal and bird life.

![]()

Education of Rural Women

Jaina basadis and mathas continued providing spiritual training to nuns (see picture no. 11). Wandering nuns and monks imparted instruction through discourses to shrāvakas or lay-listeners. Local ladies visited basadis where they learnt to read sacred books of Jaina tenets (jināgamas) and stories of sixty-three saints. Reading of puranas was arranged in temples big and small, which were attended by a good number of women. They continued to prepare cotton wicks or leaf-plates while listening attentively to recitation of sacred books. Housewives of Purandaradasa's time handled musical instrument like tittiri, mouri, tanpura, and cymbals. During festivals like janmāshthami, they assembled, sang and danced to their own accompaniments. They had their method of learning music from talented elders, who knew by heart innumerable traditional songs suitable for all occasions from child-birth to marriage, from festivals to routine household chores. Some composers like Giriyamma and Bhimavva are known to have composed hundreds of songs.

Though early marriage was in vogue, attempts were on to educate common women by arranging recitation from classics and narrating stories with a moral. Besides temples and mathas, enlightened rulers like Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar of Mysore (1672-1704 C.E.) encouraged talented women to put their education and training for public use. Sanchiya Honnamma wrote a guidebook "Hadibadeyadharma" for housewives at his stance. Honnamma was a betel-server to Devajamma, the Wodeyar's queen. The royal couple was aware of Honnamma's ability to compose poetry and suggested Aļahiya Singarārya the royal preceptor, to take her as a disciple to which he willingly agreed. Under his guidance she studied Sanskrit and Kannada classics the Bhagavadgita, smritis and shāstras.

Hadibadeyadharma contains guidelines meant for young married girls regarding running a big household. It is interspersed with anecdotes and stories from mythology to impress a point. In the colophon of her book, Honnamma implores the housewives to listen sympathetically to reading out whatever she has written, suggesting thereby that listening attentively to reading was a mode of learning among women9. There were women readers employed in palaces and other places. Oduva Tirumalamma and Oduva Honnamma were famous in Vijayanagara times.

Besides reading and reciting members, there were several hundreds of working women employed in palaces. Paes and Nuniz, the two Portuguese travelers had noticed women who handled swords and shield, who wrestled, who played various musical instruments, palanquin bearers, gatekeepers, astrologers, soothsayers and accountants. "There were others, whose duty it was to write all the affairs of the kingdom and compare their books with those writers of outside the palace" according to Paes. Naturally there must have been a sound domestic system to train women in different vocations, details of which are not forthcoming. Barbosa, another Portuguese traveler of the same period has written that the service wing of the royal palace, recruited young girls after scouting through the different towns. Sculptures and lithographs do provide examples of teachers and students (see pictures nos. 65, 66, 67). A portion of the wall-painting of Shravanabelagola matha depicts a classroom where three girls are actively responding to the teacher's query while the fourth one is looking (see picture no. 74) somewhere else.

![]()

Education of Courtesans, Prostitutes and Temple Girls

Brief mention may be made about

the training of courtesans and temple girls who continued to be custodians of

fine arts. They were not only tolerated but also respected in high society. In

Rashtrakuta times ganikas or courtesans were highly accomplished in

singing, dancing, and playing various musical instruments. They formed part of

royal entourage and received guests at important functions. According to

Manasollasa, they were present in assembly along with preceptors, courtiers and

royal members10. Dedicating dancing girls to temples for the service

of the deity came into vogue by 6th century C.E. and inscriptions as

well as Sanskrit and Kannada classics speak of their accomplishments.

From poet Dandin (6th century C.E.) to Damodaragupta (9th century), Raghavānka

(13th century C.E.) to Tirumalārya (17th century) poets were familiar

about the learning and accomplishment of courtesans. According to Dandin as soon

as the girls were old enough, they were carefully instructed in the arts of

dancing, acting, playing musical instruments, singing, painting, preparing

perfumes, arranging flowers, making garlands, reading, writing, and

conversation. In addition, they studied grammar, logic, and philosophy, which

enabled them to participate in the assemblies of the learned11.

They had to master various games.

According to Damodaragupta the ganikās in-making, had to study

science of erotics in detail, Bharata's nātyashāstra,

needlework, wood and metal work, clay-modeling, cookery, and all practical

training of music and dance.

Somanathacharitra of Raghavānka speaks of

tastefully decorated quarters of ganikas. In the evenings, they assembled

in the halls of the upper story where music concerts (sangeetagoshthis)

were held. Several indoor games like chess, dice, and gambling were arranged.

Some played veena, some taught and played with parrots, some read kāmashātra,

some sang and others danced. Some were engaged in narrating and listening

stories and satires of vilenesses of courtesans12. This class

mastered the arts of entertainment.

Basavapurana of poet Bhima speaks of various instruments played by women. They played tabor (maddaļe), blew trumpet (kahaļe), played flute, and cymbals (taļa) 13. Sculptures showing women playing all these instruments are replete.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Lady Musicians of Medieval Karnataka

Number of instruments descibed in medival literature are depicted in period sculptures

It may be surmised that some

system of domestic system to train women of different strata in the society

prevailed. The talented among them outshone when they received proper

encouragement. There were enlightened men like poet Rajashekhara (9th

century C.E.) who declared that refinement (samskara) pertains to the

soul and not to the gender. He further stated that women made good poets and

quoted from works of Vijjika of Karnataka and his wife Avantisundari in his

famous Kavyameemamsa a work on poetics.

Many women shone as administrators of cities, towns, agraharas, divisions and provinces. Queens like Shantala have become immortal because of their accomplishments. Patrons like Akkadevi and Attimabbe liberally donated towards promotion of education and learning. Attimabbe outshines in encouraging poets to write books and distribute literary works free.

![]()

References

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. X, Bowringpet 65.

- Adipurana VII, verses 58-60.

- Chourapanchasikha of Bilhana (Sanskrit).

- Prabhulingaleele VII, verses 17-18.

- Sewell, p. 362.

- Sivatattvaratnakara, VI (ii) V4, Sewell, p. 237.

- Sewell, p. 274.

- Kanthiravanarasarajavijayam, ch. VII, p. 18-31 (Kanthi).

- Hadibadeyadharma, ch. IX, verse 56.

- Manasollasa, Vol. II, verses 918-919, p. 80.

- Dasakumaracharitam, ch. II, Education of Kamamanjari.

- Somanatha Charitra, II, verse 45.

- Basavapurana, II, XII, verse 42.

![]()