Photographing Tribals

Experiences Photographing the Tribals of Bastar

by K. L. Kamat

First Published in "Timeless Theater" CD-ROM, 1999

Page Last Updated: January 12, 2026

Editor's note: The reader may find that the author at times went too far to photograph the natives, often invading their privacy. If you are disturbed by the journalistic freedom, please skip this article.

Adivasis (the tribals) are as hard to photograph as the blooming flowers, flying birds, or unavailable women. Adivasis of Bastar run away at the sight of strangers. It is common belief that a camera is a dangerous weapon, much like a gun. I didn't want to employ the authority of their village head (Mazi) or a police officer, and thus take unnatural pictures, so I developed the skill of photographing without a subject's knowledge. Many photographers from various magazines pay the adivasis to pose in all kinds of positions. Typically, they focus on provocative clothing and postures. They typically bring with them high government officials who scare the tribals into reluctantly co-operating. I didn't want to be one of these photographers, and took the hard approach.

The government has opened a tribal community on the outskirts of Narayanpur (Ghadabangal) for the pleasure of tourists. All the tribals do there is to wear skimpy clothes and pose for photographs. That's how the tribals sustain themselves.

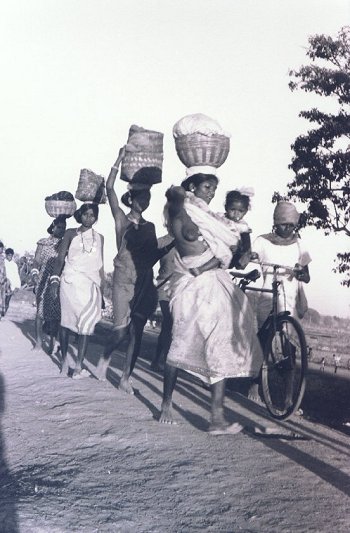

Adivasis universally love marketplaces, festivals, and dance parties; they come from afar to participate, and this provides a golden opportunity to the photographer. However, since the civilized folk misbehave with tribal women in such crowds, the women typically come prepared with a lot of clothing. So in order to get the photos I wanted, I had to return to their habitat in the deep forests. My Exacta camera had a view-finder that was like a periscope and I used it effectively to take pictures without the subject's knowledge. It would look as if the camera was hanging from my neck, but in fact, it could focus and take shots. The shore of Narayanpur lake was very narrow, as a result of which the adivasis had to walk in single file. Especially in the evening, the sun was behind the lake, providing me with a perfect studio-like setting. I would just stand there for hours together, clicking away to glory. Most tribals probably thought that either I was awaiting a partner for a rendezvous, or looking for a place to relieve myself. In Orcha, a town with no signs of modern civilization, I parked the camera under a dark tree, and used cable-release to photograph the people as they walked into a predetermined spot. In Chotedongar, I would act as if I was photographing children, while in reality, I was photographing the people behind them. I would quit only after I exhausted all my film.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Tribal Women on their Way to Market

Tribal women walking in a single file, Narayanpur, 1977

My joy would know no bounds as I developed the film in my naturally dark room. "...I wish that this beauty hadn't closed her eyes...These drinking scenes are great... I'm never going to find this dancer again..." - I would exclaim while drying the negatives. Once I was traveling by bus, and the driver stopped to buy a matchbox. There I saw a bunch of adivasis in colorful clothing. Three girls were returning from a Ghotul in all their finery. They had several decorative combs in their hair. They wore ribbon flowers and seashells. Their necks were decorated with blue, green, and red beads. All the exposed areas of their bodies had tattoos. They had on silver jewelry. Before they realized it, I had taken about ten pictures, standing in the shadow of a bush. As soon as they realized this, they ran away to sit on a bench and hid their faces in their laps. At the end of this escapade, I was concerned that the driver might have taken off without me, while in fact he was deeply engaged in small talk with his ex-girlfriend!

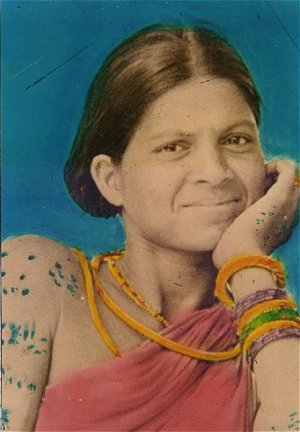

The First Lady of Bhanker

The village head of Bhanker welcomed me in all warmth and offered me tea in a leaf cup. Although his wife was fearful of the camera, she was very curious. She eavesdropped on our conversation while standing on one foot and resting her head on her palm. I could not have asked for a better pose. Every time I raised the cup in the pretext of organizing myself, I secretly took a picture. Due to the poor quality of film and chemicals I was using (the scholarship barely covered my traveling expenses), the quality of pictures did not do justice to some of my efforts, yet I have the satisfaction of trying very hard to photograph the tribals of Bastar.

When I was visited Chamerihalli's Ghotul, I found a beauty walking towards me; her mini sari, large chest, and decor were too tempting to ignore her as a photographic subject. So I changed my course of walk, found a good angle, and took what was to be my best picture at Bastar. In another place, the village head asked everybody in the town to pose for a photo. I could not refuse him, but I was out of film, and just set off the flash. They were happy anyway.

Once I wanted to photograph the half naked adivasis as they went around doing their work. Although I succeeded to some extent, because of the failing light, the photographs didn't come out well at all.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

Carefree and Free from the "Civilized" World

Tribal women walking around the village, Chindwada

If one kept the camera ready at all times, I realized, one could take extraordinary pictures at a moment's notice. While waiting for the bus, I saw several poor adivasis, who couldn't afford bus fare walking along the road. I didn't know where they were from, where they were going, their names, or anything, but I was tempted to keep their images with me forever. They were very poor, but were quite attractive. One man had as much clothing for his head as he had on the body. Another wore a bow as a shirt. One man was carrying arrack and groceries on two ends of a pole balanced on his shoulder.

I must make the mention of the rewards of being a photographer. Once two youngsters offered me an arrow and an axe for taking their pictures. Another touching incident involved a little girl who offered me five paise (equivalent of US$ 0.002 in 1997) in exchange for a photograph. Even today I regret that I could not fulfill her humble request. Next time I wish to go to Bastar with a Polaroid camera, so that I may handout pictures as soon as they are taken.

![]()

See Also: