Mortal Women and Celestial Lovers

Page Last Updated: December 07, 2024

Throughout Indian history, womanhood in all its aspects has been glorified. In traditional India, ideas of womanhood included her role as mother and wife. Although the social status of women was always related to that of her husband, their position in the household was one of authority and honor. No religious ritual was complete without her. The great Indian epics have highlighted women in these roles; a classic example is the character Draupadi in the epic Mahabharata.Women's influence was also strongly felt in the courts. In the harem - an institution shared by both Muslim and Hindu royalty and the aristocratic classes women lived in seclusion, and were specially trained in the arts of dance, music and poetry for the entertainment of the king and his nobles. These women enjoyed fine clothes, and were paid a salary according to their rank. The harem quarters were built with high walls as her privacy was held in high regard. Although such women led privileged lives, they, like their poorer counterparts, nevertheless continued to be severely restricted in a patriarchal society.

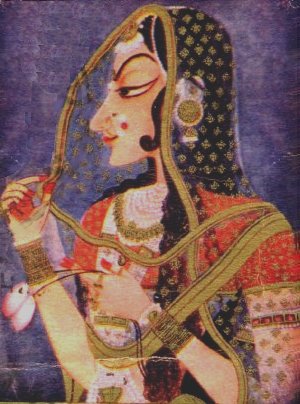

© K. L. Kamat

Indian Woman

Painting by Raja Ravi Varma

However, some royal or aristocratic women did enjoy greater freedom and indulged in male-dominated activities. During the Gupta period (4th-6th century ), women held prominent positions in the administration of the state. There were women who were involved in political affairs in later times. During the rule of the Moghuls (l6th-18th century -- see: When the Moghuls Ruled), none could surpass Noor Jahan (1688?-1645) whose strong personality supplanted even the ablest of politicians and soldiers. This trend continued up to the Vijayanagar period (14th-l6th century) with women contributing to political, social and literary activities. They were trained in wrestling and handled swords and shields. In 19th century colonial India there were queens such as Lakshmibai of Jhansi (1835-1858) and Ahalya Bai Holkar of Indore (1735-1795) who participated in wars. However, such women were exceptions in Indian history as the average women played a more passive role in society.

There were women who had the privilege of education but they were few. Before the rise of the Muslim empires, education was restricted to the Brahmin caste. The Muslim rulers however encouraged education which was available both to Muslims and Hindus. Girls usually attended the same schools as boys until puberty. Older girls were often taught privately or sent to special schools called makhtäbs. Daughters from wealthy households were taught in their homes by learned women or men. Apart from instruction in literature, philosophy and religion, girls were expected to learn the rudiments of domestic sciences such as cooking, spinning, sewing and tending to the young.

Every society has a distinctive way of looking at the most natural of human emotions - love. In India, as reflected in its art, literature, religion and culture, societies of the ancient and medieval periods were immersed in the experience and celebration of the amorous.

The ideal woman in ancient India was said to be endowed with thick thighs and broad lips, balanced by a slender waist and heavy breasts. Her lips, the tips of her fingers and toes, and the palms and soles of her feet were tinted with red lacquer. Every effort was made to enhance her beauty including countless herbal recipes. Her physical characteristics were emphasized as they were linked to notions of love, passion and sexuality.

In the Bhagavata Purana and the Harivamsa, Krishna, the grandest god of the Hindu pantheon, is extolled as the beloved of Radha and the milk-maidens of Gokul. Secular and devotional poetry alike depict Krishna as the hero and Radha as his lady love and heroine. They signify the archetypal pairs - nayaka and nayika (hero and heroine), paramatma (absolute soul) and jivatma (individual soul) where the jivatma constantly yearns to unite with the paramatma. Thus, sringara (love) and bhakti (religious devotion), two sentiments of special merit in Indian culture, share several connotations and associations. This binding of the sacred and the profane is truly singular to the Indian ethos.

© K. L. Kamat

Radha Awaiting Krishna

Rajasthani Paiting

Indian mythology is full of instances of the Gods enjoying intensely amorous exploits and what might be termed polygamous lifestyles. Ganesha, Kartikeya and Vishnu are each attributed with two consorts. Although Shiva the mighty God is depicted as a recluse of intense "other-worldliness" and terrible anger, he still falls prey to the vivacity of Mohini, and consorts with Uma, the mountain lass. Flames from his third eye devour Kama, Lord of Love, who causes Shiva to have tender feelings for Uma, destroying his state of high meditation.

One brilliant singularity of the Indian ethos is the confluence of its classical dance, music, painting and literary traditions in the theorization and depiction of love. Indian literary tradition has analyzed the essentially sentient semantics of love and classified its heroines in relation to their lovers based on their intensity of love, depth of love, expression of love, maturity of age, experience and temperament into eight types or the ashtanayikas (eight heroines) . Remarkably the theme of love treated in Indian classical literature, music, dance and painting reflects the unity of the Indian philosophy of life. Love serves as the leitmotif to this entire spread of Indian creativity.

Theories of dance, for example, consist of analyses of love situations centered on the archetypal heroine - one of the ashtanayikas. In painting, the expectant beloved waiting for the lover is often depicted in a lush bower of flowering plants and creepers (vasakasajja) while the dejected or over-anxious one is depicted suffering from the fire of passion (virahagni) and of separation. Some nayikas are also shown as deceived (khandita) and rebuked (manini) The most powerful of them all is the one who controls her lover (svadhinaopatika) with her beauty, charm and wit. The ambience in which the protagonists are depicted reflects the avastha or love-situation. In fact, the gold of the evening sky, the glade in the forest, the stream of the virgin jungle, the verdant meadows, are the visual means of expressing the literary rendering of the same theme.

Even in India classical music, the theme of love appears prominently. The variant of a raga is its feminine aspect or ragini and it is here that one returns to the theme of love, with the ragini figuring as the nayika in one of several dispositions of the ashtanayika schema.

The literary inspiration for the nayaka-nayika Paintings is the Rasikapriya by Keshavadasa and Rasamanjari of Bhanudatta, while the origins of the ragamala are in the Kavipriya. These classical treatises were written between the 14th and the 16th centuries and formed the broad matrix on which were based classical dance, music and regional poetry.

© K. L. Kamat

A Nutcraker Styled as Yaksha-Yakshi

Shashwati Women's Museum Collection

It is interesting to note the influence of the theme of love and passion on mundane objects. The refinement of the hedonistic aesthete manifests itself in objects such as combs, nut crackers, mirror-handles and locks that were imbued with erotic puns and double-entendre. This is reflective of the indulgence of the patron and the creativity of the craftsmen in uniting the mundane and the profound with earthy humor.

![]()