Food and Drinks

Food habits of pre-Vijayanagar times have with little change come down to our own days. Cookery was known as a science (Supasastra) and it developed to a finesse. Sound dietetics was a subject intimately connected with the welfare of the royalty and is discussed at length by Somadeva Suri [1]. Somesvara [1a] has devoted 268 verses to food alone, and the varieties of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes he describes are astonishing. And in ancient times, food was equated with life itself.

Rice

Rice formed the staple food of the masses; but wheat, barley (jave) and millets (jola) were also used.

Gandhasali was popular and inscriptional evidence indicates that this variety of rice was grown extensively in rural areas [3]. The Manasollasa enumerates seven types of rice and the proper way of cooking them [4]. The water used for washing rice (tandula kshalitam toyam) before cooking it was seasoned with spices; it was named vyanjana [5] and used for savoring boiled rice.

The Lokopakara and the Manasollasa mention a mode of cooking rice by removing the ambila or manda, the excess water strained from boiled rice. This way of cooking is fairly common to this day. This ambila was further used in preparing a savory known as ambila palidya by adding ground cardamom, cummin seed, pepper, clove, coriander, etc. [6]

Kalasagulu was prepared by mixing thick creamy curd with boiled rice and seasoned with cardamom, pepper and other spices [7]. Spiced rice, like kalaveya kulu [8] and huliyanna [9] were popular.

Normal Meal

Rice was eaten with soups [10] and gold-colored broths [11]. Modes of preparing soups from moong (green gram), kadale (bengal gram), lentils, black-gram, etc., are described. Several types of vegetables were used in cooking. Raw fruits (phalasaka) like plantains and jackfruit were used for curries. Tubers (kandasaka) like surana, roots like radishes (mulaka), flowers of pumpkin and plantain (pushpasaka), varieties of leaves (patra saka) and beans (simbi saka) were cooked together or separately, by adding spices or by seasoning [12]. The Lokopakara describes methods of removing the bitterness of several seeds and cereals [13].

Fruits

Fruits were grown in abundance and were used by the rich and the poor alike. This has been observed by foreign travelers to India during this period. Abu Zaid found pomegranates in plenty. Friar Jordanus (1323-1330 A D.) had noticed lemons as sweet as sugar, grapes, pomegranates, jackfruit (chaqui) and mangoes. He was of opinion that mangoes were like plums and that they were indescribably sweet and delicious [14]. Ibn Batuta, while describing different kinds of orange, says, ' ...then the sweet orange (narang) is very abundant in India. As for the sour orange, it is rare. There is a third species of the orange, which is half way between the sweet and the sour. This fruit is as large and sweet as lime. It is agreeable in taste [15].

The Somanatha Charitra mentions a typical fresh-fruit stall (navya phala vikrayada pasara) selling plantains, lemons, oranges, jackfruit, mangoes, pomegranates, jamuns (nerile), along with coconuts and sugarcane [16]. The Parsvanatha Purana adds kembale or red plantains to the list [17].

The mango was considered the king of fruits [18]. Nayasena's Dharmamrita, describing a sumptuous dinner given to a greedy Brahmin Vasubhuti, lists a number of fruits, like plantains, dates, oranges, mangoes, guavas and citrons [19]. The Manasollasa prescribes eating of fruit during dinner [20]. Inscriptions also mention the jackfruit, mango, hog-plum, plantain, etc. [21]

Sweets and Snacks

It is evident from the list of snacks in literature that the people of Karnataka had a sweet tooth. Payasam or khir was popular and it was a compulsory item of offering (naivedya) to a deity [22]. The Manasollasa recommends milk of a buffalo which has calved long back (chiraprasuta) for preparing payasa of saraveshtika (saravalige) and sevaka (sevige) or a type of noodles. This was good for lapping up (lehane yogyam) [23]. Saravalige payasa finds a glorious place in Kamalabhava's Santisvara Purana, wherein it is compared to bright autumn moonlight in which the stars (noodle pieces) were faintly visible [24]. Payasa formed an essential part of a feast [25].

The Manasollasa describes a preparation of condensed curd, sikharini. It is similar to srikhanda of Maharashtra. Water is removed from curds by straining through a cloth; sugar and powdered cardamom are added to the condensed mass [26]. Chavundaraya recommends the adding of cloves, saffron (nagakesara), ginger, pepper, jaggery and honey to it, finally fumigating with camphor [27].

Mandage (mandaka) often finds mention in literature [28]. The method of preparing it was elaborate: washed wheat was dried, ground and sieved; the flour was mixed with ghee and a pinch of salt; the dough was then rolled into balls, shaped into cakes on palms or by a rolling pin and roasted on a huge earthen pot kept upside-down and plaited fourfold, before the thin layers hardened [29]. An inscription of 1192 A.D, refers to halumandage or mandage in milk, as an offering to a deity [30].

Non-Vegetarian Food

Though a sizable population was vegetarian due to Jaina or later Virasaiva influence, a number of meat dishes described by Somesvara indicates that the nobles and the royalty were predominantly non-vegetarian. Contemporary commentaries of Vijnanesvara and Apararka on the Dharmasastras allow the use of meat under special circumstances [31]. The Agni Purana says, 'A man suffering from any sort of wasting disease should take special care to improve his appetite, and take essence of meat every day whereby he could get rid of his malady.'

Fish preparations are permitted. "There is no harm in eating such fish as pathina, rohita and simhatunda.'" Meat roasted on spits also finds place in this encyclopedic work [32].

The Yasastilaka mentions an incident in which the king Yasodhara ordered fish to be delivered at the rest-house of Brahmins, where it was to be served after being sliced and cooked. In connection with the rebirths of Yasodhara, it is told that, as a goat, he was under the care of the chief cook of the royal kitchen for a few months. Amritamati was very fond of meat and was teaching the cooks how to roast it. Finally, the young goat (Yasodhara) was also butchered for Amritamati's table [33].

Regarding meat-eating, A.L. Basham writes: 'Medical texts, even of a late period, go so far as to recommend the use of both meat and alcohol in moderation and do not forbid the eating of beef. It is doubtful if complete vegetarianism has ever been universal in any part of India, though in many regions, it was and still is practiced by most high caste Hindus [34].

According to Alberuni, sheep, goat, gazelle, hare, rhinoceros, buffalo, fish, water and land birds like sparrows, ring-doves, francolins, doves, peacocks, etc., were allowed as part of food. However, cow, horse, mule, ass, camel, elephant, tame poultry, crow, parrot, nightingale and eggs of all kinds were forbidden [35]. The Manasollasa tells about the use of pork, venison, mutton, crabs, fish and meat of rabbit, tortoise, birds and field rats, and gives details of their preparations, but is silent about eggs [36]. Paes and Nuniz, in the sixteenth century A.D., have observed that meat eating was common among the royalty and nobility, which confirms that the tradition continued through the centuries.

The nourishing and nutritive qualities of meat and fish diet were known then. In describing vegetarian dishes, the Brahmin author of the Lokopakara insists that a preparation of wheat-flour and grammash equaled meat in nutrition (mansadante balam). Similarly, peas and black gram ground together and fried in mustard oil possessed the nutritive quality of fish (matsyada gunam kuduvadu) [37].

In the chapter, 'Enjoyment of Food (annabhoga), Somesvara describes in detail the dressing and preparation of different meat dishes. According to him, the emaciated, the deceased, the old and the decrepit, children and those affected by poison should avoid meat.

In order to remove hair from the body of the pig, it should be covered with a white cloth and boiling water poured on it till the hair to be easily pulled out. Excess of hair, if any, could be trimmed with scissors. An alternate method was to smear the animal with mud and burn the skin on grass-fire. Pork steaks were either directly roasted on a spit over live coals or soaked in sour juice and cooked. These were known as sunthakas. In another preparation, the meat was sliced like palm leaves (tadapatra) and mixed with spiced curds. The slices (chakkalikas) were otherwise put in curd seasoned with sugar and filaments of citron flowers. Pork was minced to gram size, spiced with ginger, asafetida, coriander, black cumin seed (nisajiraka) and fried in oil like meat balls. Tender nispava berries, slices of onion and garlic were then added [38].

Kavachandi which was slightly different was prepared by making chopped mutton-balls in the shape of badari (jujube) fruit, mixed with some powdered spices and grains, and fried in oil. These meat-balls (vataka) at times were mixed with chopped brinjal (egg-plant), radish, onion and paste of sprouted green gram (mudgankura); they were fried and put in curry seasoned with various spices [39]. This resembles our modern kofta curry.

It is curious to note that the meat roasted on spits (sulaprotam) was as popular then in India as it is in the West today. Described as tasty (ruchyam), light (laghu) and wholesome (pathyam), this dish (bhaditraka) was prepared by boring the meat pieces and stuffing them with spices. The people knew that fried preparations, though tastier than roasted ones, were harder, to digest; that sprouted grains were good for health; that fruit and vegetables should form part of food. These are some of the examples which show that our people arrived at correct conclusions by empirical methods.

Krishnapaka was prepared by cutting meat into betel nut size and cooking in a sour mixture, spiced with hingu (asafetida), jiraka (cumin seed), camphor, cardamom and some animal blood. Varieties of mince-meat were also known. Meat-balls were popular and prepared in three ways: ground and spiced meat-balls when roasted on a hot plate were named as vatakas; when fried in oil as bhushikas and when rolled with wheat dough and roasted in live coals as kosalis. Seeds were removed from brinjals (egg-plant) and other vegetables, and they were stuffed with mince-meat and fried; they were called purabhattakas.

Panchavarni or liver gravy was prepared by seasoning liver pieces with black mustard, cooked in water, and then adding ginger, sour juices and spices. Even entrails (antrani) and heads of goats and deer were used to make curries.

Meat of birds was cooked in the same way as pork and mutton [40].

Fish was a delicacy with kings; details of dressing and frying find place in the Manasollasa. A roasted tortoise dish (nandyavarta) was prepared by removing the legs and shell and cooking in oil in a hot pan. Crab-meat was roasted on a copper pan (sutapte tamramaye patre). Meat of field rats was cooked like any other meat and seasoned with spices [41].

It is significant that meat-rice does not find place among non-vegetarian dishes mentioned by Somesvara, though rice was the staple food in the region during this period.

Drinks and Beverages

Somadeva discusses properties of fresh water in detail and concludes that it is amrita or nectar when properly used and visha or poison otherwise [42]. The Manasollasa mentions water from various sources and recommends water from rains, rivers, springs, tanks and lakes for daily use, after it is filtered through a clean white cloth. It further insists on boiling drinking water. Water exposed to the rays of the sun and the moon was not to be used at night and vice versa. It further recommends adding to drinking water pieces of mango, patala and champaka flowers, powder of cloves, camphor and sandalwood, and purifying it with triphala [43].

© K. L. Kamat

Creaming the Butter

A Medieval Sculpture from Karnataka

Different types of water are prescribed for different seasons; rain water for autumn, water from tanks and lakes for winter, pool-water for spring, spring water for summer and underground water for rainy season. The king should sip water very often during a meal; this imparts taste to the food and helps digestion. He is also advised to sip water whenever he feels thirsty, even at odd times. Leather bags (charmapatra) and earthen pots are recommended [44].

The Lokopakara describes cold drinks (panaka or sherbats) prepared from fruits like jujube (badari), myrobalan, pomegranate, tamarind and citron (madala) to quench thirst [45]. The Manasollasa also lists panakas prepared from different fruits and explains in detail the modes of preparing them. For obtaining an excellent panaka, sour juice was added to milk, the liquid part of whey was strained through a cloth and with this liquid was mixed some juice of ripe tamarind fruit. Fresh coconut water is also maintained as a tasty drink [46]. Ibn Batuta greatly relished it and he writes: 'The coconut tree is one of the most wonderful trees. One of the marvels about its nut is that if cut while yet green, one could drink its highly delicious and cool water, which generates heat and acts as an aphrodisiac [47]. The Parsvanatha Purana adds the cooling orange juice (tanirasa) and sugar-cane juice (ikshurasa) to the list of cold drinks [48].

© K. L. Kamat

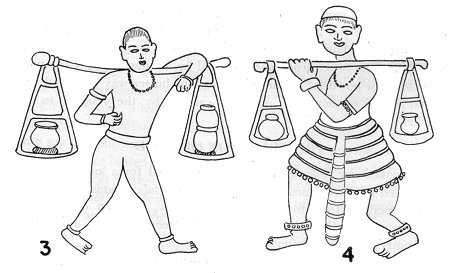

Figure 3-4: Milk Products being Carried to Marketplace

The Lokopakara describes the preparation of buttermilk (majjige) and the Manasollasa calls it a drink. People of medieval times were used to its salted and sweet (lassi) varieties, as of today. After churning the curds (Figs. 1 & 2), butter was removed and the liquid seasoned with ginger, cardamom and salt, and lastly was fumigated with hingu and jira. The sweet drink was prepared by adding sugar, cardamom and camphor powder [49]. After churning, the butter was collected and stored in cool earthen pots and was carried by the vendors to the market-place (Figs. 3 & 4).

Preservation of Food

Cooked rice (kalasogara) could be preserved for a long time, if it was boiled in water, medicated with leaves of Tulasi, madala and other plants; later, curd was to be added. Similarly, payasam of rice prepared in cow's milk could be preserved by keeping it in an earthen pot immersed in cold water [50].

Pickles were prepared of green mango, myrobalan, lime, ginger, lemon, other citrus fruits (herile), bamboo sprouts, etc., and preserved [51]. According to the Nalachampu, pickles of green and raw bilva (bellavatta) or bel, ambate, chellakai, green mango, green mango, green pepper, raw ginger, raw cardamom and myrobalan were in vogue [52]. They still are. Ibn Batuta, who had observed the popularity of pickles throughout India, explains the method of its preservation [53].

While the Manasollasa mentions the use of papads (parpatas or happalas) during meals; the Lokopakara tells of sandige (badi) and the mode of preserving them [54]. Upashandakas were prepared by sprinkling meat pieces with asafetida solution, then rolling them in salt and drying in the shade for 2/3 days. Fish preserve was also in vogue by mixing pieces of cleaned fish with salt and storing in jars (kumbha). These would keep for a long time (chirakalam vasanti ye) [55].

The Lokopakara prescribes modes by which juices of mango, citron, jackfruit, jambolana (nerile), etc., were extracted and preserved by adding pepper, rock-salt, camphor and borax (tankana khara) and exposing to the sun. Tender and green mangoes were preserved in ghee. Color and taste of mangoes remained unchanged when preserved either in jaggery syrup or honey [56].

According to Friar Jordanus, coconut honey could be used as a preservative. This was prepared by collecting the sap from the palm tree, boiling it down to one-third of its quantity which resulted in a honey-like jelly [57]. Ibn Batuta records that this coconut honey was of "great utility" and was purchased by Indian, Yemeni and Chinese merchants who transported it to other countries for preparing halwa. He had also observed the methods of extracting milk form coconuts and its extensive use by the coastal people [58].

Synthetic Food

The Lokopakara deals with the preparations of synthetic or ersatz food. Sugar could be obtained by mixing ground black lotus roots with jaggery in the proportion of 5:1 and cooking the mixture. Butter was prepared by mixing oil, curd, buttermilk and ghee in equal quantities, adding a little coriander powder. Another method was to blend teel oil, kernel of belala fruit, with an equal quantity of ghee. To obtain condensed milk, gram flour was mixed with ginger and, after warming it with milk, it was chilled. Similarly, condensed curd was also prepared. Synthetic milk was prepared by soaking grated coconut in water seasoned with long pepper (hippali), grinding the mixture and sieving it. The other method was by soaking the kernel of belala fruit in milk for 21 days, drying the mixture in shade and adding it to sugarcane juice. The quality of butter could be improved by adding powder of medicated roots to thickened milk, preparing yogurt and then churning it. Methods of preparing derivative and additive hingu (asafetida) from the basic material were also known [59].

Seasoning

Spices like green and dry ginger, turmeric, garlic, cumin seed, mustard, black pepper (melasu), bhadramuste (a kind of sedge), baje (fragrant and medicinal roots) and cloves are mentioned in inscriptions [60]. To this, the Lokopakara adds clove bark and leaves, saffron, kachora (long zedoary), cardamom, asafetida, camphor and coriander [61]. The Manasollasa enriches the list with methi (fenugreek), nisajiraka (black cumin), rajaka (black mustard) and onions for preparing meat dishes [62]. Cinnamon does not find place in these sources probably because it was not available in India at that time.

Again, the Lokopakara explains how garlic and onion could be used in different vegetarian preparations [63], though these were taboo for Brahmins and Jains. On the other hand, Somesvara recommends asafetida rather than onion and garlic for meat preparations. Rocksalt (saindha lavana) was used for specific purposes. Curd was flavored to taste.

Chillis do not seem to have made their appearance in the South Indian cuisine at the time. In the Lokopakara, we find a compound of trijataka which included powder of saffron, bark and leaves of cloves, and of chaturjataka, which in addition to these included cardamom [64].

Clarified butter was the most popular cooking medium followed by teel oil and mustard oil (sarshpa taila); in coastal regions coconut oil was used, as observed by Ibn Batuta[65].

Seasonal Food

The Yasatilaka recommends sweet, bitter and astringent food for autumn; sweet, salty and sour dishes for winter and rainy seasons; pungent and astringent varieties during spring and light food in summer. Further, it elaborates that in winter one should take fresh food, preparations of milk, pulses and sugarcane, curds and things prepared with ghee; oil too is beneficial. In spring, one should avoid heavy, cold and sweet dishes, and use little ghee. On hot days, one should take sali rice, moong soup, ghee, with preparations of lotus stalks, fresh shoots and bulbs, fried barley flour, sherbets, curds mixed with sugar and spices, coconut milk and water, or milk with plenty of sugar. In the rainy season, the food should be dry, light, oily and warm; preparations of old sali rice, wheat and barley should be taken. In the autumn, the diet should consist of ghee, moong, wheat flour, milk products, patola (species of cucumber), grapes, amalaki fruit (myrobalan), sugar, sweet bulbs and greens [66]. The Manasollasa also holds similar views and advises the king to partake of astringent dishes in spring; sweet and cooling in summer; salted in rainy season; sweet, oily and hot during autumn; and hot and sour in winter [67]. This ensures quicker metabolism of the food in keeping with the changing seasons.

Food of the Masses

Non-vegetarian food was fairly common but Jains, Brahmins and Lingayats were strict vegetarians. An inscription of 1220 A.D. records that a Jain Guru Sagaranandi subsisted on maize (jolada kulu) and butter for twelve years [68]. The Dharmamrita says that rice-gruel (ganji) is a humble fare [69]. Basavesvara sarcastically remarks that the people think of milk, butter, pulse-rice (khichadi) or jaggery as an offering to God, but that none thinks of gruel (ambali) [70]. This indicates that ambali was the diet of the poor as it is today. Somadeva describes the miserly meal of a penniless and a greedy person named Kilinjaka. It consisted of stale boiled rice, full of husk and gravel; some rotten beans, a few drops of rancid atasi (agase: flax) oil; slices of half-cooked gourds and badly cooked vegetables; gruel mixed with plenty of mustard; the beverage was some alkaline fluid tasting like the water of a salt mine; finally, boiled black rice (syamaka) mixed with buttermilk [71]. Ibn Batuta noticed that rice was the staple food of the coastal people [72]. Several foreign travelers of the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries have left detailed accounts of the commoners' food.

![]()

Table Manners

Kings and nobles sat on raised seats (gaddika). Food was brought and served in steel (loha), porcelain (rukmapingala), silver or gold vessels, plates and bowls [73]. Nuniz, in a later century, observed that kings were served food in large and small vessels and basins of gold set with precious stones [74]. In Chalukyan times, napkins or aprons (sitavastra) extending from the navel region to the thighs were used at meal-times [75].

Brahmasiva, a Jain poet, condemns the dining habits of Brahmins by pointing out that they bundled their dhoties and footwear (perhaps wooden sandals) and kept them under the seat and ate the left-over (perhaps children from their mothers') from one another's plates. This statement might be based on a limited observation of the poorer section of Brahmins attending a wedding feast or a community dinner [76].

The mode of serving and eating was common to the poor and the rich, except in quality and number of courses. According to Somesvara, rice with moong soup and ghee was served first followed by meat and vegetable preparations, sweet dishes, payasa and fruit. Panaka and buttermilk were sipped and sikharini relished during meals. Vatakas or badi (sandige), papads (happala), fish preserves, and pickles were served as side dishes. The last course consisted of rice and buttermilk with a little salt [77]. This applies to public dinners of all classes except the very poor; in the case of some castes, the courses would be sans meat and fish.

Ibn Batuta, who was entertained by the Sultan Jamaluddin, ruler of Hinavr (Honavar in North Kanara), but a feudatory of the Hindu king "Haryab", has left an interesting account of a coastal Muslim dinner. Sitting on a chair, he was served food on a copper table called khawanja, in a copper plate talam (thali), by jariya (beautiful or slave girl) wrapped in a silk sari. She would ladle out rice from a big copper vessel, pour ghee over it, add pickles of pepper, green ginger, lemon and tender mangoes. The second helping consisted of rice with cooked fowl. The third serving was another variety of chicken, also with rice. Then followed different fish preparations with rice. Thereafter vegetables cooked in ghee, and milk dishes were served with rice. The meal was rounded off with kushan or curded milk. Hot water was drunk after the meals, as cold water would be harmful in the rainy season [78]. The food habits of the aristocracy followed a regional pattern; except for the religious taboos, there was no marked difference between Hindu and Muslim repasts. The Nalachampu gives a vivid description of a wedding feast or buvaduta with all its regal magnificence [79].

Marco Polo, the famous traveler of the thirteenth century, observed that the natives of the South did not use spoons or platters but spread their victuals upon huge dried plantain leaves. He further noticed that men and women washed their bodies twice a day before meals, and used only the right hand for eating [80].

To provide shelter, food and water to travelers was considered meritorious. Ibn Batuta saw excellent arrangements for traveling from Hinavr (Honavar) to the Malabar coast. At an interval of half a mile, wooden sheds were constructed in which benches and drinking water were provided. The supervision of the water-shed was entrusted to an "infidel", who used to provide drinking water to Hindus and Muslims alike; but he poured water into the hands of the latter from a distance. Muslims could not enter the house of an "infidel" or use his vessels. Any vessels used by the Muslims were either destroyed or given away. Hindus used to cook for Muslims, where there were absolutely no houses of the latter; food was served on plantain leaves and soup was poured on it; the leftovers were eaten by dogs and birds [81].

Inscriptions commemorate construction of eating-houses (annachhatras) and water-houses (aravattiges) built on different highways [82].

![]()

Forbidden Food

The Agni Purana advises a brahmacharin (celibate) to refrain from eating unwittingly beet-root or garlic or from drinking wine. He was to avoid cakes, sushkala (dried fish), krisara (khichadi or milk with rice and pulse), partridge flesh and thickened milk... Flesh of five-digited animals such as porcupine (sallaka), iguana (godha), rhinoceros and tortoise was permitted; that of other animals was prohibited [83].

Somadeva forbids eating germinated paddy and ghee kept in a brass vessel for ten days. Bananas with curds and buttermilk, milk with salt, broth of pulses with radishes fried barley powder turning compact like curds, and sesame preparations at night were to be avoided [84].

Utensils and Other Accessories

The rich and the poor alike used earthen vessels. Somesvara recommends an earthen pot (mridbhanda) for preparing marrow soup, and hot earthen pan (karpara) for frying polikas (flat cakes) [85]. Chavundaraya mentions a wooden vessel (kashthapatra) and one of metal (sthali). From contemporary sculptures, it is evident that the technique of manufacturing earthen pots had hardly changed over the centuries (Fig. 5). Earthen pots (madake) were used for preparing payasa, storing milk and curds [86] (Fig. 6). Snacks were fried in a deep frying pan (kataha) [87]. Different types of copper and brass utensils were employed to cook, store and serve various kinds of food (Figs.7, 9, 10, 13). Coastal Muslims mostly used copper vessels (Figs. 8, 11, 12), as noticed earlier. Caste Hindus used plantain leaves and leaf-bowls for eating. The rich had silver bowls and plates [88]. Special types of bowls were used for drinking. According to Marco Polo, care was taken not to touch the vessel with the lips, while drinking liquids [89]. This method has changed little since.

Liquors

Intoxicants were considered the luxury of the nobility and the fighting castes. The Kashmiri port Kalhana mentions that king Lalitaditya's legionaries, while marching in the South, got rid of their fatigue by sipping coconut wine in the cool breeze of palm trees on the banks of the Kaveri river [90]. The Agni Purana classified wines of grape, sugarcane, palm and coconut sap, besides madhavika, tanka madhavika and maireya. Lavam sura, krishna sura and paishthi were liquors, the last being highly intoxicating [91]. The Manasollasa adds wines of palm (talimadya), coconut (narikelasava) and date (kharjurasava) to the list. The methods of brewing, these are also described [92]. Marco Polo found palm-wine delicious and says it inebriated faster than grape wine [93].

The Smritis and religious writings of the time put a taboo on intoxicants. The Agni Purana prohibits liquors to the three twice-born castes and prescribes penance for infringement [94]. By and large, the social climate did not favor the use of liquors during ordinary meals and banquets. Orthodox and Hindus and Jains abstained from drink. However, some people had succumbed to the temptation; kings in the company of nobles, ladies of the harem, as also some commoners freely indulged in drinking at the time of festivals, marriages and special occasions [95]. Women in the king's train or in the court drank freely their favorite wines [96]. It was customary for the king to pour drinks for the ladies and make them eat savory snacks. Vivid descriptions of ladies participating in drinking parties (madhupana goshthi) and their various stages of intoxication are to be found in literature [97]. Sour and salty snacks, roasted meat, onion slices, curried and roasted gram were eaten in between cupfuls [98].

The Agni Purana emphatically declares that Kshatriyas should not consume liquors but that the king should organize hunting parties and engage them in drinking bouts, in order to provide his subjects with amusement [99]. Inscriptions recording temple grants refer to the traditional number of three hundred toddy tapppers (billamunurvar) which indicates that a sizeable population was addicted to drink [100].

© K. L. Kamat

Fig. 17. A Drunken Woman being Helped by Friends

Special bowls and goblets like patra, chashka, sthalaka and karaka were used for different wines. Some of these could be identified in sculptures. In a drinking scene (Fig. 14), three couples are being served wine by male and female attendants. The housewives are shown in another sculpture chatting while sipping wine (Fig. 15). In yet another sculpture, a drunken soldier (Fig. 16) is shown. A tipsy lady escorted by her entourage is vividly sculpted (Fig. 17).

Tambula

The kings used to appoint a special officer to distribute tambula to selected persons on special occasions. The descriptions of foreign travellers and inscriptions show that chewing tambula was widely popular. It also formed an important offering to the deity. Betlenuts of the Banavasi country were famous. The betel leaves of Nagavalli and Karapura creepers and lime (chunam) of pearl oyster were considered the best. Camphor, musk, nutmeg, kakkola berry, pills of sandal paste and other spices were added to the pan. These were supposed to eliminate the noxious effects on the throat and strengthen the teeth [101]. Chewing of pan, the Indians believed, was conducive to health [102].

Betel-nuts and leaves, at times the gardens growing them, were offered to God and inscriptions record the quantum fixed in the grant. The tambuliga community which traded in betel-nuts and leaves held an important place in society [103].

Karnataka had contributed many delicacies to the country. Somesvara had even used Sanskritised Kannada names of dishes as shown below:

Sanskrit Kannada Dhosaka Dose Gharika Gharige Idarika Idli Purika Puri Vataka Vade Angara polika Kendada rotti

Current South Indian delicacies like tairvade or mosaravade and vadesambar find mention in his book.

A thousand years ago, the people of Karnataka were aware of the benefits of a balanced diet. Their food consisted of carbohydrates (rice and sugar), proteins (pulses, milk products, meat and fish), vitamins (greens, vegetables, fruits), fats (ghee, butter, edible oils), etc. The use of salads (pachchadi), sprouted gram, and pickles of green fruits, especially of myrobalan which is rich in vitamin 'C', shows that they had arrived at the correct concept of the chemistry of food. The intake of different foods to suit seasonal changes bespeaks of the attempt to attune the body to the environment.

![]()

References

- YAIC, p.112

1a. Manasollasa or Abhilashitarthachintamani. This is ascribed to the Chalukya king Somesvara III (1126-38 A.D.) - LK, VII, 1, Bhuvanadol-annamayam rana

- EC, VII, Sb. 138

- MS, II, pp. 115-16, vv. 1345-57

- Ibid, p.134, vv. 1578-79

- LK, VIII, 55

- LP, v. 62

- DA, I, 147

- PP, VII, v. 60

- MS, II, p. 135, v. 1589

- YAIC, p. 29

- MS, II, pp. 116-17, vv. 1357-69 and p. 131, v. 1548

- LK, VIII, v. 21

- FNSI, pp. 127, 199-200

- IB, pp. 17-18.

- SC, II, vv. 103-104

- PP, IX, v. 9

- AP, XI, v. 96.

- DA, I, v. 151

- MS, II, p, 135, v. 1595.

- EC, VIII, Sb.71 (1431 A.D.); EI,V, p. 22, No. 3 (1121 A.D.).

- EC, VII, Sk. 186.

- MS, II, pp. 117-18, vv. 1374-75.

- SPK, p 533.

- PP, VIII, v. 50; BP, III (xii), v. 13.

- MS, II, p. 134, v. 1574

- LK, VIII, v. 54.

- VD, p. 74; DA, I (i), v. 147; PP,VIII, v. 51.

- MS, II, p. 118, vv. 1379-80.

- SII, XX, 178, Hipparage (1192 A.D.).

- HDS, IV, p. 425.

- Ag.P., CCLXXIX, pp. 643, 1024.

- YAIC, p.38.

- WTI, p. 213.

- AI, II, p. 151.

- MS, II, pp.121-31, vv. 1415-1547.

- LK, VIII, vv. 15-16.

- MS, II, p. 121, vv. 1420-22; p. 122, vv. 1432-34, 1437. It may be noted that even today meat in curds is popular in North India. Ibid., p. 123, vv. 1440-43; p. 124, vv. 1450-52.

- Ibid., p. 124, vv. 1453-56.

- Ibid, p. 125, vv. 1464-65; pp. 125-27, vv. 1473-93; p. 129, v. 1518; pp. 129-30, vv. 1522-23.

- Ibid., p. 130, vv. 1524-31; p. 131, vv. 1537-43.

- YAIC, p. 113.

- MS, II, pp. 136-38, vv. 1601-28.

- Ibid., p. 138, v. 1624.

- LK, VIII, vv. 32, 37, 56, 57.

- MS, II, p. 134, vv. 1581-84; p. 137, v. 1615.

- IB, p. XXXVII.

- PP, ix, V. 36.

- MS, II, p. 135, v. 1596; pp. 133-34, vv. 1572-73.

- LK, VIII, vv. 3-4.

- LP, v.63.

- NC, vv. 462-63.

- IB, p. 181.

- LK, VIII, v.17.

- MS, II, p. 129, v. 1515; p. 130, vv. 1533-34.

- LK, VIII, vv. 32-38.

- FNSI, pp. 200-01.

- IB, p. XXXVIII.

- LK, VIII, vv. 39-47, 68-71.

- EC, VIII, Sk. 186; EI, XIX, No. 4 (1135 A.D.).

- LK, VIII, vv. 53-55.

- MS, II, pp. 121-31, vv. 1415-1547.

- LK, VIII, v. 26.

- Ibid., vv. 5, 6, 10, 44, 48.

- IB, p. XXXVIII.

- YAIC, pp.112-13.

- MS, II, p. 136, vv. 1598-1600.

- EC, XV, p. 22, No. 201 of c. 1220 A.D. of Ballala II.

- DA, XIII, p. 203.

- BLV, p. 17.

- YAIC, p. 29.

- IB, p. 181.

- MS, II, pp. 134-35, vv. 1585-87.

- FE, p. 363.

- MS, II, p. 135, v. 1588.

- SP, XIV, v. 154.

- MS, II, p. 135, vv. 1589-97.

- IB, pp. 180-81.

- NC, vv. 441-47.

- TMP. p. 371.

- IB, p. 182.

- SII, IX (i) 235; XI (ii) 137; XV 151; XX 101.

- Ag. P., CLXVIII, p. 643.

- YAIC, p. 114.

- MS, II, p. 118, v. 1383; p.128, 1508.

- LK, VIII, v. 4.

- MS, II, p. 118, v. 1384: IB, p. 180.

- PP, VIII, v. 60.

- TMP, pp. 358-59.

- RT, IV, v. 155.

- Ag.P., CLXXIII, p. 661.

- MS, III, pp. 215-17, vv. 431-49.

- TMP, p. 378.

- Ag.P., loc. cit.

- MS, loc. cit.

- VC, XI, vv. 44-48.

- MS, III, p. 215, v. 428; KK, I, p. 429.

- MS, III, pp. 216-18, vv. 443-64; PB, IV, v. 87.

- Ag.P., CCXXV, p. 805.

- SII, XV, 211 of 1196 A.D.

- MS, II, pp. 83-85, vv. 959-78.

- TMP, p. 376.

- SII, XI (ii) 152 Hosur, 'garden of betel leaves'; 167 Yalisirur, 'garden of betel nut';172 Sirol, 'tambuliga settis'.

![]()

See Also:

- Kitchen Simmer Masala Meatloaf Recipe -- Creative Indian style meatloaf recipe

- Can You Make Meatloaf Without Eggs -- Egg substitutes for meatloaf recipes

- Food Habits of Vijayanagara Times -- Research paper explores the food habits of Indians during the Vijayanagar times, using references in period literature, archaeology, and travelogues.

- Old Time Parties -- Drinking habits of men and women of Karnataka as described in medieval texts and sculptures.

- Social Drinking in Ancient India

- Topics on Indian Food